Last year marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of poet James Galvin’s Elements, one of the most durable and essential poetry collections of its era. Born in Chicago and raised in northern Colorado, Galvin is the author of several celebrated collections of poetry, including, most recently As Is; a novel, Fencing the Sky; and a book of prose, The Meadow, which has been called “one of the best books ever written about the American West.”

The conversation that follows was conducted over the course of several weeks; due to spotty internet at his cabin near Tie Siding, Wyoming, Galvin drove into town so he could respond to questions from the Spic and Span Wireless Laundromat. The poems included below appeared originally in Elements, and can be found now in Resurrection Update: Collected Poems, 1975-1997, published by Copper Canyon Press. —Chris Dombrowski

Chris Dombrowski: We just passed the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of Elements. You must have written it thirty or so years ago—can you recall what you were reading at the time and in what places you composed the poems?

James Galvin: At that time, I was teaching at Humboldt State University in California, “behind the redwood curtain,” an incredibly beautiful land- and sea-scape. I was probably trying feverishly to fill the gaps in my not-so-rigorous education. I think I was discovering the metaphysical poets, and I was teaching, among other things, prosody, and the combination of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s devotion and his fabulous prosodical inventions was dizzying. I remember I was considering various scansions of a Hopkins line and I walked in front of a bus. I didn’t get hit but—that poor bus driver—there was screeching of brakes and adrenaline all over the street. I’m sure I was still reading all the great poets born around 1925: Merwin, Wright, Justice, Ashbery, and I was emerging from my Marxist-Leninist “training” to discover Merrill—a mind-boggling poet who I at first resisted for stupid reasons having to do with Class. Turned out I was the pretentious one.

Perhaps I should also mention that I was building my house up here in the mountains during those years—all hand-work, starting with cutting down about a hundred standing dead trees. I used a double-bitted axe, a cross-cut saw, and an auger.

Chris: Did that kind of ground-up construction inform the way you made the poems in Elements?

James: Well, I never thought about it before, but it must have. I wanted to make some kind of tribute to an old way of doing things in a beautiful and straightforward way. Also, I didn’t have any money. That could be a parallel too. Trees are free if they are on your property. They are like the alphabet.

I had to be willing to take a very long time and put a massive amount of work into something plain. I made big, open rooms and put in a lot of windows to give them light and a feel of lightness, though the materials are anything but light. I had to keep my tools very sharp. I wanted to make something that looked like it had a right to be there, in this landscape. The poems in Elements are meant to be elemental—trees and an axe—and weightless, not philosophical juggernauts. They have to assert their right to be there. But the weight that goes into making a poem is everything you have read in your life, right?

Not So Much On the Land as In the Wind

Not so much on the land as in the wind,

From where I stand the nearest tree is blue.

The house is log and built to last. It has—

Past the souls who tried to make a life here.

One huge overshoe and a galaxy

Of half-moons gouged into the linoleum

Where someone’s father tipped back in his chair

In counterpoint to the wind’s sad undersong.

He knew the wind was grinding his life away.

Now roof nails bristle obscenely where shingles have flown,

And the blown-out panes all breathe astonishment.

The leaning barn is only empty sort of.

It harbors rows of cool and musty stalls. Dark stalls

That haven’t held a dreaming horse in years.

I turn to leave, turn back to latch the gate—

Odds on the past to outlast everything—

I walk toward the tree to make it green.

Chris: The speaker in “Not So Much On the Land as In the Wind” alludes narratively to an old cabin: “Odds on the past to outlast everything.” What, if anything, does this line have to say about poems?

James: There’s a lot of sky out here, and any building that is going to last has to withstand a lot of wind and weather. It has to be grounded to live in the wind. Like any good poem, which, I suppose, has to live in both books and minds.

As for “Odds on the past to outlast everything,” that is partly a dig at what presents itself as novel or experimental. Every avant-garde thinks it is the last avant-garde. It never is. Also, I love aphorisms, even though they’re tough to handle. William Blake’s are undoubtedly the best, because they seem at first outrageous and then irrefutable: “It’s better to murder a babe in the cradle than to nurse unsatisfied desires.” He is not advocating infanticide. Or Goethe: “Colors are the deeds and the sufferings of light.” That one is so speculative it’s hard to argue with, and it’s so beautiful one doesn’t want to. One doesn’t want to sound like a know-it-all.

That line of mine wants to be true, but it’s also kind of a throw-away. It’s too obvious to take itself seriously. And Antonio Porchia has a wonderful book of aphorisms. I may have been thinking of him.

Chris: Your remark reminds me of the first few lines to “Post Modernism,” the closing poem in Elements: “A pinup of Rita Hayworth was taped / to the bomb that fell on Hiroshima. / The Avant-garde makes me weep with boredom. / Horses are wishes, especially dark ones.”

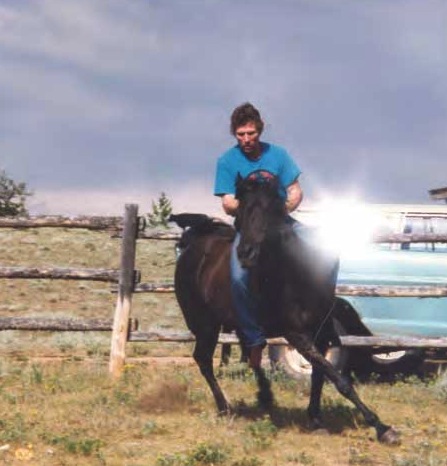

Can you say a little something about your relationship with horses here? Have you been around them your whole life? You’ve written so eloquently about them in Elements and elsewhere (I’m thinking of “Stories Are Made of Mistakes” and “Putting Down the Night,” among others), and I’m wondering if your horses (caring for them, riding them) play into your poetic practice. I imagine they’re pretty severe critics.

Post-Modernism

A pinup of Rita Hayworth was taped

To the bomb that fell on Hiroshima.

The Avant-garde makes me weep with boredom.

Horses are wishes, especially dark ones.That’s why twitches and fences.

That’s why switches and spurs.

That’s why the idiom of betrayal.

They forgive us.Their windswayed manes and tails,

Their eyes,

Affront the winterscrubbed prairie

With gentleness.They live in both worlds and forgive us.

I’ll give you a hint: the wind in fits and starts.

Like schoolchildren when the teacher walks in,

The aspens jostle for their placesAnd fall still.

A delirium of ridges breaks in a blue streak:

A confusion of means

Saved from annihilationBy catastrophe.

A horse gallops up to the gate and stops.

The rider dismounts.

Do I know him?

James: Well, I wrote that poem a long time ago when I felt like there was an avant-garde. I don’t feel that way now. The fashion then was fragmentation and refusal—what seemed to me to be a self-congratulatory kind of cleverness backed up by massive amounts of exposition. Everyone was afraid to admit that those hyper-rational movements didn’t make us feel anything. They weren’t supposed to because sensibility was held to be suspect. So I thought that a bombshell of one kind juxtaposed to a bombshell of another—one relatively harmless, the other anything but—had a kind of postmodern aspect, a very sinister pre-postmodern aspect, that was unthinkable, but not boring.

Horses. Yes, I have been around horses all my life. In one poem I wrote, “My father thought nothing/ Of putting his children/ On rank horses./ We did child-breaking research/ On ground.” He had a very old-fashioned approach to breaking and riding horses. Now we’re gentle with them. We treat them like kindred spirits instead of like trucks. But the more I think I understand about these magical creatures, the more mysterious they seem. They mediate between people and the wild. Out here they live in nature, but they let us ride them. The rural West has been a horse-based culture for over four hundred years.

In this country, taking care of cattle means training and riding horses. They herd, they cut, they let us rope. Why? We are predators, they are prey. Who domesticated whom? Why do they let us ride them? They don’t have to. They belong to that category of things people don’t deserve, like leverage and sailing into the wind. They are strong, they are gentle, they are emotional, they are amazingly athletic, they are beautiful. I have already started talking about why horses are like poetry. Why do poems let us write them? They mediate between us and everything we don’t understand, not just nature, but the wilderness of our emotions and ideas. They take us places. They change our minds. Horses don’t need to read poems because, like poems, they are poems. We don’t deserve either.

Chris: I recall Anton Chekhov saying in a letter, I think to his brother, that if one is going to write about the natural world, he had better do it in such a way that the landscape becomes a character in and of itself. I would argue that in Elements, the landscape is one of the main characters. Would you buy that notion?

Chris: I recall Anton Chekhov saying in a letter, I think to his brother, that if one is going to write about the natural world, he had better do it in such a way that the landscape becomes a character in and of itself. I would argue that in Elements, the landscape is one of the main characters. Would you buy that notion?

James: Absolutely. No argument. Chekhov is right. I think I started to use the natural world (let’s not try to define that term) as a character in and of itself earlier on, but in a kind of innocent way. I just thought that besides love and death it was the biggest thing there is. I now think it is bigger. In my first two books the natural world is a character—it has characteristics, it speaks—but it isn’t until Elements that things like weather and terrain really act on human emotions and ideas. Eventually I would write a prose book called The Meadow in which I consciously tried to make a landscape and a weather-scape the protagonist of the book, with the people more or less blowing through.

But writing landscape as character is not easily done. Geology and geologic time don’t really care about anything as far as we can tell, and most characters in literature care about something. The cares of charcters at odds with each other is what makes stories. Despite its infinite and intricate sense of balance, the natural world remains aloof. We want to love it, but it won’t love us back. It seems beneficent and murderous by turns. It has no purpose. It just is. That is a hard character to draw. I know a lot of people reading this will disagree with what I’m saying, but it’s what I think. Our job, it seems to me, is to love that ruthless magnificence, to let it inhabit us until it turns us inside out, to be awed by it’s matchless beauty and its merciless devastation. Kind of Old Testament, no?

Emerson said somewhere that God is not God. God is the life of God. We see Him most clearly in nature. I wonder if Robert Frost ever came across that bit. And what is our purpose? To destroy everything? If so, we are doing a bang-up job. I think the world would be better if we devoted ourselves to awe, in love, in art, in nature.

Chris: “Returned to eternity,” Donald Revell wrote, “all poetry is prophecy.” I recalled this line the other day at lunch when I was stung on the tongue by a bee. When the swelling finally decreased I was struck by the fact that I had, in my first book of poems, written about a young man who was once stung by a bee on the lip. This isn’t the oddest meshing of art and “real life” I have ever experienced, but it does lead me to ask you: have any of the poems from Elements had strange afterlives?

James: I don’t think there is anything with an afterlife as literal as your bee sting, but when I read that book now I see that the love poems in it knew something that I didn’t know when I wrote them.

At the time I was married and had a daughter. Like everybody who gets married, I thought my marriage would last. When I wrote those love poems, I was just trying to write good love poems, but when I read them now I notice a hint of melancholy in them, which seems to prognosticate the end of love. It says love’s not love until it’s lost. That relationship dissolved ten years after I published Elements. It’s as if, without my knowing it, that melancholic tone prophesied love’s end.

Chris: Well, as you say in one such poem: “Mystery moves in god-like ways.” Though this also makes me think that there’s another kind of love poem in the book, an ode, of sorts, to admiration and wonder. I’m thinking of “Coming into His Shop from a Bright Afternoon,” in which the speaker enters the blacksmithing shop of a friend who is hard at work. With its mythic undertones, this poem, made almost entirely of images, has always seemed emblematic to me of the artist’s task—in fact, a much-lauded poet from your generation once told me he thought the poem was the finest ars poetica written in the last fifty years. Can you talk a little bit about this poem?

James: On one level, the poem is documentary. I really did come into a blacksmith’s shop on a bright afternoon. When I entered the almost subterranean darkness, I couldn’t make out anything. As my eyes adjusted, a seemingly infinite number of objects gradually appeared. It still amazes me to think of the superb creations that came out of that Blakean shop—guns, violins, jewelry. So the ars poetica aspect is unavoidable. It’s not about any particular poetic; it’s more about what it means to be an artist. You work the bellows, keep the iron hot, and swing the hammer. You sweat. As far as the mythic dimension, you have Hephaestus, yes, but also a more familiar creator.

The poem begins with stars, and ends with iron from the earth. And hammer blows like bells. Whether it’s mountain ranges and oceans, or individual species, nature thrusts everything back into the fire when it loses its blush. It keeps making everything over. I don’t know if I knew about global warming in 1988, but now we know it’s getting hotter.

Chris: I want to go back to something you said earlier: “Why do poems let us write them?” Is this a sentiment/wonderment you’ve held for a while? I mean, it strikes me that many contemporary poems seem, well, conquered by their authors, rather than encountered, accepted. And to that end, do you see a poem as something you are making, something you are allowing to be made, both?

James: Poetry offers itself to us as a way of talking about the things we can’t talk about. No one invented it. It was given. In our primitive attempts to make poetry memorizable, we discovered that it could be memorable. Great poems are smarter than great poets. The language is smarter than anyone who uses it, and the language of poetry, with its architectures and musics, is the most sophisticated form of verbal expression. The idea is to give your self over to the language of poetry—let the language speak for itself. This involves a process of self-annihilation, which is necessary to negative capability. Negative capability—being comfortable with ambiguity and paradox—is how you avoid being one of those poets out to conquer the poem.

Because of poetic syntax, which is inseparable from expressive rhythm, we can get, “Bright star! would I were steadfast as thou art—” where Keats is expressing more through the rhythm of that memorable line than he is expressing semantically. The poem let him write it. Poetry also leads us to revelations that are, without it, beyond us. In Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium,” the distance travelled between “Whatever is begotten, born, and dies” and “Of what is past, passing, or to come” is measured in light years. Further more, once the poem lets you write it, it isn’t done with you. A great poem is a different poem, a smarter poem, every time you read it again.

So, yes, I have always had this feeling that the next poem already exists, it just isn’t written yet. You have to wait for the poem to let you write it. I think it is not unlike the way Michelangelo could look at a block of marble and see the singular figure already extant inside it, waiting to be freed. The sculpture is already there in the stone, it just hasn’t been created yet.

Am I waxing mystical? Maybe. But the mystery of poetry, its inexhaustible surprises, subtleties, and exfoliations of emotions and ideas made me that way. A great poem exceeds any poet’s ability to write it.

Chris Dombrowski’s most recent collection of poems is Earth Again. His essay “Chance Baptisms” appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of Orion.

Comments

25 years since “Elements” (wow, really?) Galvin’s still got it.

Thanks for this.

John

You’re welcome, John T. It looks like the formatting on “Coming into His Shop…” got scrambled in the ether-world, but we’ll get it fixed quick. Sorry for the scramble….

Thank you, Chris. Thank you, James. This is it. And Chris you led to the “its” revelation.

Jack