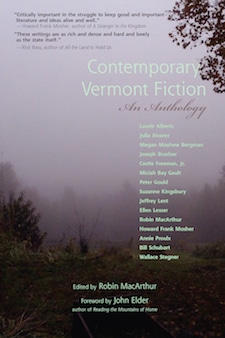

Late last year, Green Writers Press published Contemporary Vermont Fiction, an anthology of short stories from and about the state that features work from several Orion contributors and friends. The editor of the anthology, Robin MacArthur, is an Orion contributor herself; her piece “Sugaring” appeared in the March/April 2012 issue. Watch a trailer for the book below, and order your copy here.

Late last year, Green Writers Press published Contemporary Vermont Fiction, an anthology of short stories from and about the state that features work from several Orion contributors and friends. The editor of the anthology, Robin MacArthur, is an Orion contributor herself; her piece “Sugaring” appeared in the March/April 2012 issue. Watch a trailer for the book below, and order your copy here.

How did this anthology come together? What was the collection process like, and what made you want to take on the project of reading, selecting, and publishing?

This anthology had been gestating inside me for about twenty years before Dede Cummings, the founder of Green Writers Press, and I decided to make it happen. I grew up on the same piece of land where my dad grew up in southern Vermont, and I’ve always been on the lookout for writing, and specifically fiction, that portrays the complexities of this place that I know and love. Vermont has such an interesting history: our landscape is agricultural and rural and yet tucked between the urban centers of New York, Boston, and Montreal. Because of this there’s long been tension between those who have been here for generations and those who have flocked to the state as tourists, or who came during the homesteading and commune movements of the 60s and 70s. I grew up with a hyper-awareness of these cultural clashes and these tensions, and when I was in my late teens, I began seeking out fiction that illuminated these various class dichotomies and tangled webs.

In 2013 I ran into Dede Cummings, a neighbor of mine, who had recently started a new press dedicated to environmentally conscious writing. I immediately knew I wanted to work in some capacity with Green Writers Press, and this book seemed like the perfect fit. I began reaching out to some of the authors whose work I had loved for years, and seeking others whose work I hadn’t yet read. In selecting work for the anthology, I wanted to include as diverse a pool of voices and perspectives as I could find. I wanted to include the voices of the Abenaki people, of those who had been here for generations, of hippies, of homesteaders, of the French Canadian population here, of migrant workers, and many others. The magic of an anthology is that you get to put these voices together, within two covers, and host a broader vision of place than any one author could ever create.

Tell us about some of the stories presented here. Do you have any favorites, and did you find any stories or authors that were new to you?

Oh, it’s so hard to pick favorites! Some of the stories I had known and loved for years. I’d long been enamored of Wallace Stegner’s beautiful story, “The Sweetness of the Twisted Apples.” It’s about an artist couple driving around the back roads of the Northeast Kingdom in the 1950s and the way they romanticize and aestheticize the harsh poverty they encounter there (and are also changed by it). There’s amazing compassion and tenderness within his lines. I also knew from the beginning that I wanted to include stories by Annie Proulx (who lived here in the 70s and 80s), Jeffrey Lent, and Howard Frank Mosher.

But many of the other stories I included were new to me. Julia Alvarez, after some courting, wrote an amazing original story for this anthology. The piece, “A Light Out: A Vermont Story in Five Voices,” masterfully portrays a range of perspectives regarding the influx of migrant farm workers in our state. Joseph Bruchac has a wonderful, magic-realist piece about an elderly Abenaki man who is fed up with contemporary politics and begins conversing with a deer, who eventually saves his life. Megan Mayhew Bergman’s story, “Night Hunting,” captures the thin line between Vermont’s habitability and its wildness. The last piece I found for the book was Peter Gould’s story, “Horse Drawn Yogurt,” which masterfully (and humorously) portrays the naiveté, passion, and good-heartedness of the hippies who flocked here to live on communes in the 1960s. But really, I could go on and on. I love them all.

You’re a native Vermonter, with a relationship to the state that goes back generations. But what might us outsiders learn from these stories? Might someone from another part of the country find something in here that rings true, even if they’ve never been to Vermont?

Vermont holds such a unique place in our contemporary cultural narrative; it’s branded and idealized as being the promised land for the organic food movement and progressivism, and criticized for its cultural homogeneity. There’s truth to all of that, but the picture is also more complex. I hope that these stories enlarge the narrative of what Vermont is, and who Vermonters are, for both Vermonters and those outside of the state.

But I hope the book has more universal relevance as well. First off, these are beautiful stories. Second: place-based anthologies, by their very nature, illuminate how limited our own understandings of place are, and thus the importance of broadening our perspective by hearing the stories of others. I personally love reading place-based fiction about places I’m not from and places I’ve never been. It’s a way of travelling without leaving home, and also a way of knowing a place deeper than one could by simply passing through. Put those stories and those anthologies together, and we broaden our understanding of the world and of those who inhabit it.

Did anything surprise you as you pulled this collection together? Did you encounter any themes, resonances, or insights about your state that you didn’t expect?

I love thinking about the way that our landscapes shape our writing. Barry Lopez once wrote that we are permanently altered by the architectures we encounter at a young age, and I agree, and would extend it to say that we’re altered by the landscapes we settle within. You can’t live in Vermont and not be influenced and affected by the natural world around you, and that connectivity shows up in every story: ice storms, deer, coyotes, lakes, wildflowers, wild apples.

I also love witnessing the commonality of the landscape in these stories, primarily the ways in which all of the characters stand on the threshold between the urban and the wild (as Vermont itself does). In many of the stories that urban world is looming, whether it’s in the hearts of youth who want to escape their backwaters, or the coveted and powerful wealth of those who live there.

You write in the book’s Introduction that “art might be the most influential and powerful tool there is to enact profound cultural change.” Can you unpack that idea a bit, and tell us how it finds expression in the book?

To be quite honest, I’ve lived in fear that someone would ask me this question since I published that line. Because it’s quite a statement to make! But I think I truly do believe it. The power of narrative is strong; we won’t understand other people, or their perspectives, until we hear their stories, and feel those stories in our bones. I recently did a reading for this anthology for the seniors in my hometown and some of the most staunchly conservative, old-time Vermonters were there. I talked about this cultural divide, and they bought the book, and I thought: wow, these people might read Peter Gould’s story about the hippies and witness, for the first time, that the hippies are just as good-hearted and humble and good-intentioned as they are. And if those walls can dissolve, then maybe the cultural divide, which has morphed into a political divide, and (tragically) turned into an environmental catastrophe, can begin to crumble. Of course this is one miniature example, but change sometimes happens in small instances like these. As I say in my introduction in the book: I’m an idealist. But I still think that’s the power art has—to allow us to see the humanness of others and let go of our foolish political battles. We all want the same thing: a good life for our children and grandchildren on a planet that is thriving.

On another front, these stories are about people whose lives are, in various ways, wedded to the land and the natural world around them. I’m also a believer that anytime we read narratives in which human lives are entwined with the natural world it has the potential to shift our values, if incrementally. Narrative has the power to help someone say, hey, there are other things I could be doing with my life right now other than buying things or watching TV. Stories have the power to bring people back into a sensory awareness of the earth around them, and with that entanglement and connectivity comes caring, and with caring comes (we hope) action.

Is that bullshit? I don’t know. But I want to believe it. We should all try to do our part to try and make the world a more socially and ecologically conscientious place. Green Writers Press has a quote across the top of its website by the Senegalese environmentalist Baba Dioum that pretty much sums it up: “In the end we will conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand.” I love this place where my family has lived for three generations, and where I’m raising my children. I love the world. I love my neighbors. I want them to be loved, to be cared for.

Comments

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.