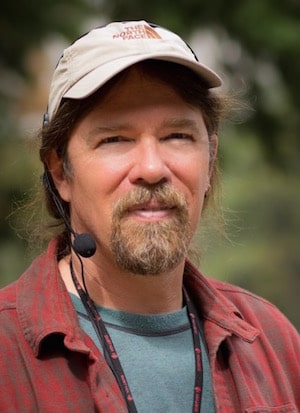

David Lukas is a professional naturalist and author of six books, including the just-published Language Making Nature: A Handbook for Writers, Artists, and Thinkers. This book expands Lukas’s past writing about birds and natural history into wholly new territory—an exploration of techniques for creating new words to bring the richness of language back into our lives. Orion editor-in-chief Chip Blake asked him a few questions about the book.

David Lukas is a professional naturalist and author of six books, including the just-published Language Making Nature: A Handbook for Writers, Artists, and Thinkers. This book expands Lukas’s past writing about birds and natural history into wholly new territory—an exploration of techniques for creating new words to bring the richness of language back into our lives. Orion editor-in-chief Chip Blake asked him a few questions about the book.

Chip: Dave, you and I have known each other for a long time, and I mainly think of you as a hot-shot birdwatcher and expert naturalist. How did you arrive, then, at the idea of writing a book about language?

David: The funny thing is that I arrived at language directly from my study of plants and animals. From an early age I started wondering about those weird-looking scientific names attached to every common name and for me they came to symbolize some kind of secret key into the magical kingdom of scientists. I soon discovered that you could break these scientific names into their Greek and Latin components, and that these pieces told small little stories. So I became comfortable with the idea that you could break words into pieces and use those pieces playfully, and as I grew up it was natural for me to continue doing this as my experiences and questions about the world deepened. The book tells the story of why these word-making pieces and processes are valuable tools for leading us toward the visions we want to create.

Chip: Can you give an example of such a “small little story”?

David: The scientific name of the yellow-headed blackbird is Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus, which means “yellow-headed yellowhead.” It’s a fun new way of thinking about this colorful bird!

Chip: A number of recent books (like Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks) investigate the ways in which the loss of vocabulary that describes landscape diminishes our experience of the world. Your book is related to that, but pushes in an additional and more proactive direction: that by creating new words, we might create new ways of thinking about, or even solving, the many urgent problems we face. Tell us more about how that might work.

David: Yes, many books have bemoaned the loss or diminishment of language and Macfarlane does an amazing job of capturing finely nuanced old words and making them appealing again. My goal is to take this one step further by turning word-making into an art and an exercise that is both playful and highly creative. I believe that if we start “sketching” and playing and experimenting with words as if they were malleable and open to our imaginations, then our language becomes juicy and fun again. And when language has a lot of juicy material to work with it starts to shift and sift out jewels that challenge our thinking and endure over time.

My understanding is that words are vessels which are filled with meaning, and when those meaning-spaces are filled we can’t easily use those words to convey new meanings or values. Thus, if we think of lumber or plywood or paper when we hear the word “tree” then it becomes very difficult to use that same word to communicate other, deeper values. New ideas, new values, and new visions for the future require new words to carry those new meanings—our task then is to create new words that lead the way forward.

Chip: Some years ago you studied Barry Lopez’s papers at the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library housed at Texas Tech University. Barry’s a master of language about the natural world. What kind of effect did that work have on your thinking about the relationship between words and natural history?

David: I spent two months immersed in the University’s archive of eight-five boxes of manuscripts, drafts, and audiotapes on a Formby Fellowship. Barry’s thinking about language and landscape is highly formative. He asks a lot of important questions, and then models in his own thinking and writing, how language and landscape inform each other. This asked me to go deeper in my own questions. For instance, I have been reading for years that we “need a new language of nature” and I started wondering why someone didn’t create this language. Barry courageously tries to answer questions, even when there’s no right answer, so this inspired me to answer my own question.

Chip: How has your immersion in thinking about language changed your experience of being in the field?

David: I live in language now. When I look at the world I no longer merely see trees and rocks and mountains; I now see fragments of words, I see threads and webs of history and meaning, I see a malleable and claylike media that my mind is constantly engaged in playing with. It’s a bewildering (in the true sense of the word “be-wild-ering”) and exciting way to engage with the world. One of my long-term goals is to start leading nature walks that focus on language, where we explore nature and web effortlessly through linked etymologies and word fragments as if we were exploring a natural history of the mind.

Chip: Can you imagine ways that readers might use this book? What have you been seeing and hearing since it was published?

David: I imagine this book as a user’s guide that combines practical tools (lists of prefixes and suffixes, lists of word elements, lists of contributions from older languages, etc.) so it can be used as a reference, alongside highly readable sections about the deep power, energy, and potential of language to express our experiences. As a naturalist, I love books I can carry with me in the field and that is the goal of this book—that it can be used to inspire and guide new thinking about language in the field, in the moment when readers are most open and curious about the world. Already I’m getting e-mails from people who are using the book to create new words, or have started book clubs to discuss and play with these ideas—that’s it, that’s how culture is created and moved forward, word-by-word, conversation-by-conversation.

Language Making Nature is available directly from the publisher through Amazon.

Comments

This is a very interesting book. I have bought several copies for myself and friends.

Loren Eiseley was a master of the language of natural history. When I was doing salmon habitat research in the Methow I often tried to imagine a hike with Eiseley up the Chewuch or Twisp creating Methow prose.

I love it.

Any way to integrate experience and create meaningful relationships within our world,

and between various life forms has the potential to create relational healing, planetary harmony.

This is inspiring,

Thank you!

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.