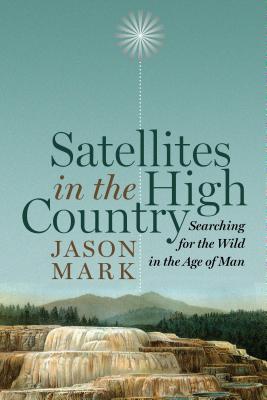

Since its inception, environmentalism has been concerned, one way or another, with the concept of wildness. The nature and identity of what’s wild—and the question of how humans ought to relate to it—is the subject of constant, and constantly shifting, investigation on the part of people who are interested in the interface between nature and culture. In his new book, Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man, author Jason Mark pulls these questions into the modern context of climate change and the global reach of human civilization, and attempts to locate wildness wherever it still resides.

Since its inception, environmentalism has been concerned, one way or another, with the concept of wildness. The nature and identity of what’s wild—and the question of how humans ought to relate to it—is the subject of constant, and constantly shifting, investigation on the part of people who are interested in the interface between nature and culture. In his new book, Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man, author Jason Mark pulls these questions into the modern context of climate change and the global reach of human civilization, and attempts to locate wildness wherever it still resides.

As a journalist of middling stature (at best), I’ve grown used to ephemerality. A writer labors alone, head down, trying to tease a story out of a jumble of facts and determined to trick sentences into lines that will slip into the reader’s mind. Then the piece—essay or detailed reportage or measly blog—is cast into the great maw of the media. Maybe the piece is greeted by a wrenching silence. Maybe it manages to make a slight ping—a twenty-four-hour burst of Twitter mentions and Facebook likes. And then the labor of love evaporates into the ether of ones and zeroes, or is dropped into the recycling bin. Even when writing for, say, The New York Times, all the hard work will be wrapping fish tomorrow.

So it came as something of a surprise when, in December 2012, an essay of mine ignited something of a firestorm in the community to which I belong—that is, the San Francisco Bay Area environmental scene. My article, “In Defense of Drakes Bay Oyster Company,” was part personal essay, part just-the-facts-ma’am journalism that offered some opinions on a seven-year-long battle over the fate of an oyster farm in California’s Point Reyes National Seashore. I wrote: “It seems to me the debate over the ecological impact of Drakes Bay Oyster Company is all backwards. The issue isn’t whether shellfish farming is compatible with the ideal of wilderness. Rather, it’s whether a wilderness is compatible with the pastoral landscape that surrounds Drake’s Estero.”

The blowback was withering. One reader, a veteran environmental attorney in San Francisco, said the piece was “intermittently childish … ignorant … and myopic.” The executive director of a Northern California green group called the essay “stunningly disappointing” and said I should be “ashamed” of writing it. Another reader said he was “gobsmacked and appalled” that such an argument appeared in Earth Island Journal (where I was then editor), which was founded by the legendary twentieth-century conservationist David Brower. A few readers came to my defense, fueling a heated online exchange that stretched for months.

The intensity of responses didn’t surprise me. I had been following the Drakes Bay Oyster Company controversy for a while, and I had seen how it had divided people of similar values. On one side of the oyster farm controversy were folks with solid environmental credentials—people like farm-to-table pioneer Alice Waters, writer Michael Pollan, and scientist Peter Gleick—who felt that the oyster farm represented the best ideal of the green economy: a family-owned business, producing food for the local economy, and in a manner that had a (relatively) light ecological footprint. According to this point of view, we could have our wilderness and eat it, too. On the other side of the issue were most of the major environmental groups—the Center for Biological Diversity, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Sierra Club—who argued that the oyster farm should go, and the estuary in which it was located restored to how it looked for millennia. By the time I wrote my essay, the controversy had become so red hot that it had split apart friendships and families in the bucolic communities north of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Still, even if the response wasn’t entirely surprising, the intensity of the emotions was shocking. The oyster farm controversy seemed so parochial—a battle royale over bivalves!—and yet it had driven a wedge deep within the environmental movement (at least in Northern California). I couldn’t help but notice a vibe of defensiveness—a sense of persecution almost—among some commenters, a fear that the longstanding passion for wilderness had been cast aside as environmentalists increasingly focus on the existential threat of climate change.

The old faith in the value of wildness appeared to be melting under the glare of a hot, new sky. For many people—including those who would call themselves environmentalists—human self-preservation had come to trump the preservation of wild nature. For others, however, such a reorientation was akin to surrender. “If this is the New Environmentalism, I want the old … kind back, thank you very much,” one commenter wrote.

The oyster farm controversy had cast into sharp relief some of the most difficult questions about our relationship to Earth. What do we expect from wild nature? Wilderness on a pedestal? Lands that we garden and tend? Or something in between? And perhaps the biggest question of all: with the human insignia everywhere, is there any place—or any thing—remaining that is really, truly wild?

***

To answer those questions, I spent a couple of years traveling to some of the most rugged and remote places in America. In the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, I floated down the Aichilik River to the shores of the Arctic Ocean, on the way encountering caribou herds in biblical proportions, a giant red fox displaced by climate change, and one overly curious grizzly bear. In the Gila Wilderness of New Mexico, I tracked the Mexican gray wolf, one of the most intensely monitored and managed wildlife species on the planet. I went to a Paleolithic “ancestral skills camp” in the eastern Cascades, where I learned to start a fire with two sticks and how to brain-tan deer hides. In the Olympic rainforest, I tried to experience one of the quietest places in the Lower 48 (a place I had first read about in Orion).

Those travels, and others, became the basis for my book, Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man. In the end, what I discovered surprised me. And, if you read the book, I think it will surprise you, too.

My most important revelation was discovering that “wild”—along with “wilderness” and “wildness,” those cornerstones of modern American environmentalism—doesn’t necessarily mean “pristine.” In fact, it never has.

Go back to the etymology. Wild comes from the Old English wildedéor, or wild deer—the beast in the woods. Go further back into the etymology and the meaning becomes more interesting. In Old Norse, a cousin of Old English, the word was villr. “Whence WILL,” my Oxford English Dictionary says, meaning that wild shares the same root as willfulness, or the state of being self-willed. A description lower down the dictionary page makes the point plain: “Not under, or submitting to, control or restraint; taking, or disposed to take, one’s own way; uncontrolled. . . . Acting or moving freely without restraint.”

Notice that there is nothing about being “unaffected” or “untouched”—words that have more to do with the pristine than with the wild. Rather, the meaning centers on the word “uncontrolled.” To be wild is to be autonomous, with the power to govern oneself. The wild animal and the wild plant both rebel against any efforts at domestication or cultivation.

Here, now, in what some scientists are calling the Anthropocene—the Human Age, or the Age of Man—this distinction between “untouched” and “uncontrolled” is more crucial than ever. With the evidence of human civilization everywhere—from nuclear radioisotopes scattered in the geologic record to satellites embellishing the firmament—there is no pristine nature left. There is no wilderness that’s completely untouched. We live in what you might call a “post-natural world.”

It is much more useful, then, not to ask what is natural, but to seek out what is wild. Because even in its diminished state, the wild still holds a tremendous power. When we search out the wild, we come to see that there is a world of difference between affecting something and controlling it. And in that difference—which is the difference between accident and intention—resides our best chance of learning how to live with grace on this planet.

In short, what I have been preparing to say is this: I was wrong about the Point Reyes Seashore oyster controversy, an error that only became apparent to me as I wrote my book.

***

The word essay comes famously from the French essaier, which means “to make an attempt.” Satellites in the High Country is very much a book-length essay, an attempt to figure out what wildness means today. At its best, an essay should feel like a journey. The writer arrives at some place different from where she began, and the reader comes along for the ride, a hitchhiker of sorts.

For me, there were the actual journeys to wild places and then, happening simultaneously, the intellectual journeys. Eventually, my original glibness gave way to the complexity of facts on the ground. Ultimately, my views began to change.

Any decent book, whether fiction or nonfiction, should prompt the reader to look at the world differently. And even if a book doesn’t completely blow the mind, it should, at the very least, cause the mind to bend in new and unexpected ways.

I’d like to think that readers who make the commitment to Satellites in the High Country will come away from the book with a new, expanded understanding of humans’ relationship to wild nature. Especially for those readers who consider themselves environmentalists, I’d hope that the book would force them to reconsider their assumptions about wilderness and wildness in the twenty-first century.

I don’t think that’s too immodest of an aspiration. After all, I know this: In the writing of it, the book changed my mind.

Satellites in the High Country was published by Island Press in September. From 2007 to 2015, Jason Mark was editor of Earth Island Journal. He is now the editor of SIERRA, the national magazine of the Sierra Club.

Comments

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.