NATASHA NOWAK’S strong arms strain to hold Chunky Chip in position. “He’s probably the third largest one we’ve ever had,” she says. Chunky Chip, whose shell is the size of a gladiator’s shield, weighs forty-eight pounds. He’s so big and powerful that Natasha and her partner, Alexxia Bell, need to use an electric screwdriver to secure, and then remove, the screws holding the lid shut over his gigantic stock tank.

As Chunky’s scaly, clawed feet whirl, Natasha, forty-four, grips the turtle’s slick carapace while she perches on the swivel stool near the operating table. With her right hand, Alexxia, forty-six, pries apart the turtle’s sharp jaws with a gynecological tool. An array of surgical instruments await nearby, but none is more important than the object for which Alexxia now reaches: a champagne cork. She pops it into Chunky’s capacious gape. The cork does double duty: it keeps the turtle from biting and props his mouth open for the coming procedure, which must be done while he’s awake. With a patient like this, anesthesia is avoided whenever possible.

Yesterday, Alexxia drained an abscess from a puncture wound left by a fishhook—the larger of two wounds that brought Chunky here from the Marblehead pond that had been his home for perhaps the past hundred years. He now has several new pockets of pus inside his mouth that need draining. Alexxia touches one of them with a dental instrument. Chunky lunges, nearly dislodging the cork.

Then Alexxia’s cell phone rings. She grabs it from a holster on her leg and wedges it between shoulder and ear. “Hi, Mom!” she says. I hear her mother’s cheerful chatter on the other end, until Alexxia cuts her off. “Let me call you later, okay?”

Mothers are used to hearing their grown daughters say they’re too busy to talk, but Alexxia has the perfect excuse: she’s doing oral surgery on a very large, wild, and fully alert snapping turtle.

THIS TIME OF YEAR, the phones are always ringing: A Good Samaritan has found a snapper hit on the road with a broken shell. An animal control officer is coming with a painted turtle chewed by a dog. A volunteer retrieves from a pond a snapping turtle with the bolt of a crossbow through the neck.

Each spring is nonstop crisis management at Turtle Rescue League—ever since Alexxia and Natasha established a hospital for freshwater turtles and tortoises in the basement of their suburban home in Southbridge, Massachusetts.

Amid all the other houses on the street, their two-story saltbox stands out: It’s a blazing, neon green. It bears a sign in front that reads, “Turtle Lover Parking Only. Violators Better Shut the Shell Up.”

Parked in the drive are a white smart car and a black Scion. Both are mounted with strobe lights—like the ambulances they are. Emblazoned with the Turtle Rescue League logo, and with stickers urging fellow motorists to stop for turtles on the road, the cars serve as emergency vehicles for transporting injured turtles to the thousand-square-foot turtle hospital that occupies the basement—and that may house, at any one time, between two hundred and a thousand turtles.

I first visited the hospital three years ago, attending the then annual “turtle summit” to learn about the latest advances in the rarified field of turtle rescue and rehabilitation. With me that day was my friend, turtle lover and wildlife artist Matt Patterson. We both nurture a special love for turtles. At that time, Matt had four of them at home, including Eddie, a sixteen-year-old female Sulcata tortoise who could live more than a century and grow to more than one hundred pounds, and Polly, a three-toed box turtle with whom he has lived longer than with his wife. Everything about turtles delights us both: their beautiful shells, their slow pace, their ancient lineage. Turtles arose during the same era as dinosaurs, and yet are still with us. At a time of convulsive change, they promise us patience and continuity.

But today, turtles are among the most severely endangered group of animals in the world. Of the approximately 250 species of turtles on Earth, 61 percent are either extinct in the wild or threatened. They’re menaced by habitat destruction, pollution, disease, climate change, and a virulent illegal trade that targets them for food, medicine, and pets. They’re hit by cars, shredded by mowers, chewed by dogs.

The very thought of a turtle being hurt nearly broke us; the idea that we could help them was a balm.

With slides projecting in the background, Alexxia told us the story of one of her patients, a female snapping turtle. The entire first third of her shell was shattered, three of her legs were smashed, one eye was gone. She had been lying on the side of the asphalt road where she’d been hit, cooking in the sun, for hours. But two years later, that turtle returned to the wild, healed. “What looks like a fatal injury to some animals may be survivable to a turtle,” Alexxia told the assembled crowd. “If the turtle’s organs are not smeared all over the road, you might be able to save her.”

And actually, even if a turtle is dead, they can still help. If it’s a gravid female, which it frequently is—the quest to lay eggs is what sends many turtles across busy roads—Alexxia and Natasha can harvest the eggs from the corpse, hatch them in one of the hospital’s many incubators, and release the babies to the wetland that the mother called home.

The very thought of a turtle being hurt nearly broke us; the idea that we could help them was a balm.

IT’S MAY 2020, and nearly 1.8 million Americans have come down with the novel coronavirus, over 100,000 having died from it. Offices and manufacturing plants are shuttered; retail outfits shut down. Playgrounds, public pools, athletic fields, bars, casinos, gyms, museums… all closed. When Matt’s dad got sick, Matt couldn’t accompany him inside the hospital but had to drop him at the door. Nor could my husband and I see his mother, who was in lockdown in a nursing home. But Turtle Rescue League is one hospital where we can enter. At a time when the world feels like it is shattering, we come here to do our part to help pick up the pieces.

Entering the front door, we step over a knee-high wooden barricade to the living room. We are soon met with one reason for the barrier. Pizza Man, a twenty-year-old, twelve-pound red-footed tortoise with a knobby black-and-yellow shell, is headed toward us like a slow-motion missile. High-stepping on columnar legs, his toenails tapping softly on the wooden floor, he holds his pale yellow bottom shell tall as he paces determinedly across the room. He stops two inches from my feet. He jerks his wizened-looking head to the right, holds it still for a second, jerks his head back to the center, then jerks it to the left. He then swings his neck back to center and stares up into my face.

Such a spirited reaction from a turtle might surprise some. “Turtles don’t need intelligence,” the field biologist Alex Netherton asserted, “so they do not waste energy on it.” Because turtles are famously slow and spend considerable amounts of time stock-still, it’s easy to get the impression they don’t think, or feel, or know much.

Nothing, Alexxia assures us, could be further from the truth.

“This turtle really loves attention,” Alexxia explains. I bend down to stroke Pizza Man’s soft, outstretched neck and head, admiring the red patches on his cheeks and nose and his soulful, dark eyes. Then the tortoise marches on to meet Matt. If anything, Pizza Man’s ardor grows. Matt, as usual, is wearing flip-flops, and Pizza Man makes a point of standing directly on the skin of Matt’s feet as he performs his greeting.

“Pizza Man always wants to be wherever I am,” Alexxia says. Hundreds of turtles are in residence here—turtles recovering from illness or injury, turtles relinquished by previous owners and awaiting new homes, native baby turtles who hatched out late or too small, turtles who were born deformed or are permanently disabled and will live here forever. Among them, Pizza Man—who was suffering from a severe respiratory ailment when he was rescued from the basement of a drug dealer—is one of very few whom Alexxia considers a personal pet.

The other is Sprockets, a thirty-pound Burmese mountain tortoise. At age twelve, he’s not even a third the size he’ll reach at maturity. He may live for another 150 years. With a dark, boxy head and prominent beak, he comes plodding on legs as scaly as a Monterey pine cone out of the first-floor bathroom at the very same moment that Natasha descends from the office upstairs.

Sprockets’s emergence as Natasha enters the room is no coincidence. Sprockets is as devoted to her as Pizza Man is to Alexxia. Belonging to a species native to Myanmar, Malaysia, Thailand, and Sumatra, Sprockets was found on a September day in 2014, wandering around Institute Park in Worcester, Massachusetts. His owner had dumped him. “He was so nervous,” Natasha remembers. “Every inhale was a quaver, and he hid in a corner.” But once Sprockets settled in at the League, he would fall asleep on Natasha’s lap. And soon, she says, “he started telling us his life story, vocalizing and bobbing his head. He would vocalize for twenty minutes at a time!”

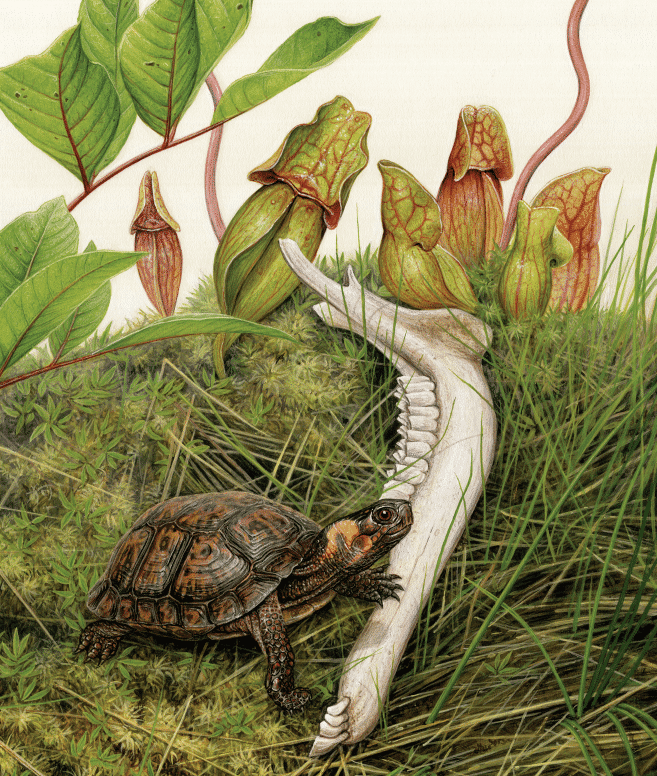

Illustration by Matthew Patterson

I had always thought of turtles as silent. But, as I was soon to learn, much of what I thought I knew about turtles was wrong. Snapping turtles, for instance, are usually pretty chill; I would quickly learn how to pick up even the largest of them safely. Within weeks, Matt and I would come to know one enormous snapper, Fire Chief, so well we could feed him by hand.

Turtles are unlikely, surprising animals. Some breathe through their butts, some pee through their mouths. Some stay active under ice-covered waters; others climb fences and trees. Some are red, some are yellow, and some change color dramatically once a year. There are turtles with soft shells; turtles with necks longer than their bodies; turtles with heads so big they can’t retract them; turtles whose shells glow in the dark.

Some species of turtles, as it turns out, can be quite talkative. Various species croak, squeak, belch, whine, and whistle. (When Velociraptors bark at each other in the film Jurassic Park, it’s the sound of tortoises having sex.) South American river turtle nestlings even communicate vocally with one another and their mothers while still inside the egg, showing a social sophistication of which few researchers, until recently, thought turtles were capable.

Natasha describes Sprockets’s voice as “a grunt crossed with air being released by a party balloon.” He’s not as vocal these days, she tells us, but he still bobs his head when he is particularly interested in a visitor. “He’s very excited to meet you,” Natasha tells us.

Because turtles lack mammals’ facial expressions, it is difficult for humans to see their emotions. The ancestors of humans and turtles diverged some 310 million years ago. Yet, a person can, with attention and practice, learn to read their sometimes subtle, sometimes alien signals.

“We get to know them,” Alexxia explains. “The personalities start to shine. It’s an unspoken communication. But it’s real.”

This communication is what fuels Turtle Rescue League’s extraordinary success in saving, and often releasing back to the wild, thousands of turtles who otherwise would have died—including many injured so badly that even veterinarians specializing in rehabilitating wildlife would have felt they had no choice but to euthanize them. “The vast majority of vets and rehabbers aren’t able to dedicate the time, space, or patience to turtle patients that Alexxia and Natasha do,” says Mark Pokras, DVM, a founder of Tufts Center for Conservation Medicine and former director of Tufts Wildlife Clinic. “I think it’s their specialization and deeply felt caring that really make the difference for so many of their patients.”

THE MINUTE WE OPEN the door to the basement, we’re engulfed in seventy-five-degree warmth and the scent of hundreds of turtles and tens of thousands of gallons of water, conjuring the warm, green funk of a quiet pond in summer.

At the bottom of the stairs, the first thing we see is the surgical theater: spotless aluminum exam and operating tables; a high-intensity light and a magnifying viewer; a Doppler ultrasound machine that can estimate blood flow through the heart and blood vessels; storage areas for surgical instruments, bandages, vet wrap, and syringes; scales for weighing turtles large and small; blackboards listing meds and procedures scheduled for various patients; a fridge and freezer for storing foods and meds; a stacked washer/dryer; a deep double sink.

As we round a corner, Alexxia raises her voice above the hum of pumps and filters to introduce us to some of the patients and residents: “This is Sergeant Pockets,” she tells us. Basking under a heat lamp beside the ramp leading to his fifty-gallon pool—his long, wrinkled neck extended—Sergeant Pockets lacks the red “ear” patches that give his species its common name. His nearly black shell is nine and a half inches long—enormous for a male. “He’s over fifty years old,” Natasha explains. He’s named after the agent who found him during a raid in Boston, where he was being offered to grocery stores for sale at $3.47 a pound. “He had pneumonia and metabolic bone disease, and couldn’t use his rear legs,” Alexxia tells us. “He’s a non-native species, and he can’t be released. He’s here with us forever.”

On another shelf, opposite the Sergeant, lives Percy, a three-toed box turtle with an exceptionally smooth, domed shell and piercing red eyes. He’s also a lifer, in a spacious habitat with a peat moss substrate, plastic plants, several shelters, and a soaking tub. Dr. Barbara Bonner, a veterinarian venerated for her turtle rescues, had found him at a Massachusetts pet store, very ill from living on a concrete slab surrounded by water—completely inappropriate for a woodland turtle. Alexxia lifts him from his habitat and sets him on the concrete floor. To our astonishment, like a windup toy, Percy instantly runs toward Alexxia and Natasha’s part-time assistant, eighteen-year-old Michaela Conder. As she scoots backward in play, she can barely keep up with the approaching centenarian.

“He’s a remarkably old turtle, having made the century mark,” Natasha says. “And he’s still in his prime!”

Christopher Raxworthy, associate curator of herpetology at the American Museum of Natural History, would agree. “Turtles don’t really die of old age,” he once told the New York Times. The major organs of a hundred-year-old turtle, he said, are indistinguishable from those of a teenager. Their hearts can cease beating for long periods without damage. In species that hibernate (brumation, for reptiles), turtles can survive, buried in mud, for months without taking a breath. In fact, if it weren’t for infection or injury, the curator said, turtles might just live forever.

But in a landscape dominated by humans and their machines, there is almost no escape from trauma. A survey by State University of New York biologist James Gibbs estimated that in the U.S. Northeast, Great Lakes, and Southeast regions, in areas crisscrossed by roads, at least 10 percent—and perhaps as much as 20 percent—of the adult turtle population is killed by cars each year. A New Hampshire study found that along high-volume roads, adult female turtles faced an 80 to 100 percent chance of being killed while traveling to or from their nesting grounds.

This is what almost happened to Snowball, a young female snapper who weighs perhaps ten pounds, with a large, teardrop scar on the front third of her top shell. In her small, shallow stock tank, she’s so immobile that she looks dead. Her head tilts markedly to the right. She came in June 2017. “She had been hit by a car and dragged,” Alexxia explains. “She was handed to us by another rescue group, who couldn’t figure out how to help her.” Her back foot was so badly mangled that most vets would have amputated it. Alexxia removed three toes, cleaned her wounds, replenished her fluids, repaired her shell. She fought infection with injections of antibiotics. She fed her by inserting a tube down her throat and into her stomach.

But time itself is the only thing that might heal her head injury. “Snowball has neurological issues; sometimes she just flips over,” Alexxia tells us. One night, after she’d been in the hospital for six months, Snowball flipped over in the water and drowned. “I put her on the Doppler to check for heartbeat and I’m getting nothing,” Alexxia remembers. “So, she’s dead. What have I got to lose? I take her out and put a tube down into her lungs and I’m breathing for her. The next thing I know, I’m getting a beep on the Doppler. I recovered her heartbeat.”

In a few hours, Snowball opened her eyes. Later that day, she showed some weak movement in her toes.

“It took three months to get her back to where she was before she drowned,” says Alexxia. “She’s like 40 percent there, mentally, now.”

“I think she’s making progress,” adds Natasha.

“Perhaps half a percent improvement each month,” Alexxia replies. “She’s a slow train crawling up a big hill.”

In the tank next to Snowball is Chutney, a somewhat smaller but still impressive male snapper who came in April 2018 with a similar problem. The car that struck him wounded his top shell, broke his jaw, and concussed his brain. “He was a roller,” says Alexxia. He kept rolling over onto his back in his hospital box—and because snappers use their heads to flip themselves upright, Alexxia would have to reset his broken jaw each time. “Any other clinic would have euthanized him,” Alexxia says. There was thought to be no hope for a case like Chutney.

Alexxia and Natasha tried taping him down so he couldn’t roll. The tape didn’t hold. They tried to weight down the top shell, but they couldn’t safely put enough pressure on his broken carapace. They had to find another way. So they came up with an ingenious solution: they slid the snapper inside a Tupperware pitcher just wide enough to accommodate his shell. “The handle acted as a kickstand so he couldn’t roll,” explains Natasha. And because the pitcher was transparent, Chutney could still see around him; when the world stopped spinning, he would know. They called their invention The Chutney Tube, and it kept him upright and safe for four months—until he didn’t need it any more. One day this spring, Chutney will be released.

“A brain injury is something you can recover from,” says Natasha. “But the turnaround is long.”

Illustration by Matthew Patterson

PATIENCE IS SOMETHING Natasha and Alexxia have learned from the turtles.

It has taken them more than a decade to get their turtle hospital to this point. The two met twenty-one years earlier, at a fashion store where Natasha was the manager and Alexxia had applied for a job doing makeup. Though opposites in many ways—Alexxia, a flashy extrovert who partied at Boston dance clubs till dawn; Natasha, a soft-spoken introvert who enjoys video games and data—they both loved animals. One of Alexxia’s earliest memories growing up in Millbury, Massachusetts, was watching her dad help a snapping turtle cross the street. When Natasha was little, her family took in orphaned and injured wildlife, including a raccoon, a woodchuck, and a seagull, at their North Oxford, Massachusetts, home.

One spring day, while the couple was headed for a date hiking on a local trail system, they found a turtle on the road, crushed but still alive, in obvious agony. They euthanized it. The next day, they saw another—unharmed, but marooned on the cloverleaf interchange of two highways. They picked it up and released it in a pond. “We kept finding turtles,” remembers Alexxia. “So instead of hiking, one day we said, let’s find turtles and help them cross.”

They created posters and flyers telling others how to help, too. But they kept finding turtles hit by cars, run over by lawn mowers and hay mowers, chewed by dogs, or afflicted by disease from neglect or poor care from people who had bought them as pets or had taken them from the wild.

“With an injured turtle in front of us,” Natasha tells us, “we didn’t know where to go. If we brought every one we found to a wildlife clinic, it would overwhelm them.”

“At the time, we couldn’t do basic shell repair,” Alexxia says. “But we learned.”

At a time when the world feels like it is shattering, we come here to do our part to help pick up the pieces.

The two women soon found themselves living with seventy-five rescued turtles and half a dozen thirty-gallon stock tanks crammed into an 860-square-foot, two-bedroom apartment in Webster, Massachusetts. To run that many filters, heat lamps, and full-spectrum lights eclipsed the rooms’ electrical capacity, and they had to run an additional conduit line—which, fortunately, Alexxia (who now owns her own appliance repair business, which in part funds the turtle rescue) knew how to install. They slept under a kayak (essential for water rescues) suspended from ropes over the bed. Friends who’d visit would ask, “But where do you girls live?”

For these women, caring for turtles is more than a job, more than a charity. It’s a devotion. “When I work on the bench with the turtles, I’m glad my parts don’t fit them,” admits Alexxia. “In a season or two, I’d be out of parts. My blood, my bones—I’d give it to them.”

PERHAPS THE GREATEST gift the turtle hospital can give its patients is time. Because everything takes a long time for a turtle.

They live slowly. They breathe slowly. (In cold water, an olive ridley sea turtle can hold its breath for seven hours.) Their hearts beat slowly, sometimes, as with the red-eared slider, just one beat per minute. During the turtle summit, we were astonished to learn how slowly the patients here react to drugs. Many analgesics are useless, because a painkiller that would work on a mammal in seconds or minutes could take hours or even days to take effect on a turtle.

Turtles also die slowly—so slowly that The Turtle Hub, a web page advising turtle owners on proper care, includes a video titled “5 Ways To Tell if Your Turtle Is Dead.” A 1957 newspaper article recounts that the heart of an alligator snapping turtle caught by a college student in Marianna, Florida, kept beating for five days after the turtle was decapitated. For reasons like this, at Turtle Rescue League, Alexxia and Natasha never declare a turtle dead until rigor mortis sets in or they detect the smell of decomposition.

Turtles have taught them that there is always hope.

“Every year we get at least one miracle turtle,” says Alexxia. One year, that turtle was Gill, from Gill, Massachusetts. Alexxia estimated he might weigh forty or fifty pounds. “When I went to pick him up, it was like you go to pick up a rock and it’s really Styrofoam. He was only thirteen pounds! A skeleton with a shell.”

A large wound on Gill’s shell had healed—but was sloughing patches of skin. He smelled like he was dead. His back legs and tail weren’t moving.

Alexxia and Natasha took him to a wildlife clinic. The staff recommended euthanasia. But the couple wanted to give Gill a chance.

What was wrong with him? Alexxia pieced together his story, which she read in the scars of his healing shell: “The year before,” she explains, “he had been hit by a car. He crawled across the road and found a patch of grass and sat there. For a year. With no food, no water, nothing. And when a turtle starves, the body doesn’t replace its cells. The body conserves everything.

“When he finally got food, he could replace those cells he was sloughing,” she continues. “But by then, the biome of his gut was messed up, so he couldn’t get much nutrition. So we fed him whole foods. Entire fish, for example.”

Gill’s back legs started moving. He gained weight. He stopped sloughing skin. He smelled better. Two years later, Alexxia phoned her friends at the clinic: “You know that turtle that was almost dead? I’m releasing him tomorrow.”

There’s hope, too, for the two young spotted turtles, unnamed, who came in last year. These gorgeous little animals have jet-black shells spangled with small yellow dots, like a starry sky reflected on dark waters. Once common throughout the Northeast, they are now listed as federally endangered, having lost half their population in a single turtle’s lifetime. One is a female with a shell crack and a rear leg problem; the other is “cognitively blind.” Her eyes look normal, but when she was about to be released after several weeks of rehab last year, Natasha recounts, “She was staring outward—but not taking in the visual world.”

Natasha could identify with that spotted turtle, because she, too, is blind.

This came as a surprise to Matt and me. Inside her own house, where we first met her, Natasha didn’t need her white cane. We had noticed that behind her delicate, bejeweled glasses, her gray-blue eyes never looked at us straight on, but instead from the side. But we thought she was just shy.

“I’ve not been out very long about being blind,” Natasha confesses. Others in her family also have retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disorder that causes gradual loss of the light-sensitive tissue in the back of the eye. She has always been determined to use what vision she has as long as she can. She first studied mechanical engineering in college, then switched to art photography. She still takes photos, but with a phone camera; she also does beautiful carpentry. She uses adaptive technology. She finds workarounds: when she reaches into a turtle’s hospital box or tank, we need to tell her which is the front end of the turtle.

What she lacks in sight, she makes up for in insight. Learning that the spotted turtle was cognitively blind during a planned release, she tells us, “We stomped back out of the woods and went home. But that doesn’t rule out eventual release.” There are plenty of turtles in woods and wetlands, she assures us, with healed wounds, with one eye, with a misaligned jaw, or only three legs. And that doesn’t stop them from living their wild and precious lives.

“All you need is one good eye,” Natasha says. “If she can eventually recover enough brain function to see out of even one of hers, she’s ahead of me!”

Nova, another blind snapper, has an even worse problem. She hatched from eggs incubated at the hospital, collected from a mother who lived in a badly polluted pond. Not only is she blind, but her day–night cycle is also now a full week long. She sleeps only if she’s upside down in her dry hospital box. Today coincides with the start of her weeklong sleep. Alexxia plucks her from the water, and the turtle struggles, “air swimming” with her back feet and swiping at her eyes with her front. But then Alexxia deftly flips her over on her back, lays the turtle in her warm, dry hospital box, and places a plush turtle stuffie on her bottom shell. Instantly, to our amazement, the turtle relaxes. Nova has lived here for seven years. Her disability is almost certainly permanent. But here, Alexxia and Natasha do their best to give Nova the chance to live her best possible life, for as long as she lives. They consider this not a chore, but a privilege.

“Turtles never give up,” says Natasha. “You never see a turtle looking defeated.”

This story was made possible with the support of Merloyd Ludington Lawrence. Excerpted from Travels in Turtle Time, written by Sy Montgomery and illustrated by Matt Patterson, due out in fall 2023 from HarperCollins.

Comments

Thank you. I just love turtles and people like these women.

Having just subscribed to Orion Magazine, this is the very first article I’vr had the pleasure of reading. My husbsnd snd I have lived in a variety of different states across the country following r careers. I have fond memories of stopping r car and carrying turtles off the road (hopefully to safety!).

What beautiful human beings r Alexia and Natasha. I wish I could meet and personally thank them for the gifts they bring to r world. This is a beautiful love story in so many respects. My decision to subscribe to Orion Magazine apparently a brilliant one and lovely surprise.

Thank u all to being part of the best of the world’s work.

So amazing. I feel so useless.

The turtles are amazing creatures, who knew?

The women who love and care for these animals are extraordinary.

Extraordinary is not even close to who they are.

Have they established a non-profit of any type? I would love to donate some funds to them and their amazing work. Even if they’re not a non-profit, I would still send them some funds. Thank you for. This amazing story. I have (unbeknownst to me at the time) a male and female pair of African Leopard Tortoises. They came from the very first clutch in the US over 30 years ago out of San Diego. Dr. Tom Boyer sold them to us. I still have them and they are amazing and loving additions to my household. Their names are Norton and Trixie. Since I don’t support breeding of Reptiles (even though thats how I got mine), the conditions of their enclosure are not ideal for procreation. Trixie’s (very hard) slugs are not fertile and will never materialize into baby tortoises. Norton is smaller and has never been able to connect to her cloaca (thank god). I wish you both much continued to success and joy in your quest for saving turtles/torties. This planet really needs more kind and caring souls like you both. Blessings on a continued successful journey. Gina

God bless you. Hopefully some philanthropist funds your worthy cause so you can really focus on the care and not worry about overhead. Ideally there could be a network of places like yours, a franchise across America serving this need.

Extraordinary ladies with heart and soul dedicated to saving lives. Kudos.

Stunning example of the highest powers in the human–and turtle!–species; thank you so much for what you do, for sharing, for who you are.

Cool

To Turtle loving ladies and gentlemen. I have a male and a female Pacific Pond turtle. the female was rescued off of the hot pavement on a basketball court with her tail burnt off. I built a habitat for Pacific pond turtles complete with fish and a waterfall. my turtles are very social. Their names are Tucker the male and Spud the female. Recently a small turtle was noticed swimming in the pond just hatch. we made a habitat to protect the small quarter-sized turtle which my mom named Two Bits. We have been studying the Pacific Pond turtle and found out that only one in a 1000 hatchlings make it to adulthood. There is a Pacific Pawn turtle rescue in Washington where they are an endangered species. We are proud to give them equality habitat with a loving quality relationship with them. I would love to see the setup the ladies have for all the turtles. My sister lives in Florida where I saw lots of turtles on the side of the road. I thought they were dead but maybe I was wrong. Thank You

I have been fortunate to be able to meet and spend time with Natasha, Alexxia and Mikaela and to personally witness the excellent care they provide to their turtles and tortoises. They are dedicated and compassionate people and I am so grateful for all they do. To see the care they provide, and to witness the successful rehabilitation of some very sick and injured turtles is really inspiring. Since meeting them I have adopted three turtles and they have helped me every step of the way. When I first met them, I knew very little about turtles. Now, I can’t get enough of them. I’m hoping to adopt a couple more this year! Thank you Natasha, Alexxia and Mikaela for all you do. You are truly amazing people and I will always be grateful for your friendship, and for the amazing work you are doing.

Extraordinary story of extraordinary creatures loved by extraordinary people.

Thank you.

Thank you so much for this article about the amazing work being done by these powerful women. We owe you a great debt of gratitude, thank you for all the time, energy, patience, and expertise you put into this labor of love for turts. Wow, just wow. Fabulous article, beautiful artwork, what a joy to read. Your gifts are blessings for the planet and its creatures. Our two rescue turtles: a three-toed male with a shell scar and one eye has been making our life meaningful for 26 years now, and a female gulf coast boxie has been cheering him on for over 14 years. He was abused and near death and she had been hit by a car and was hiding from nearby tormentors. When they came into our lives we had no idea that they would be the ones rescuing us! Life with them everyday gives our personal struggles over the years such meaningful joy. We were guided by an amazing woman Tess Cook btw. Bless you all for making this difficult compassionate work happen.

This is a wondrous article about incredible creatures (the women and their turtle friends) and I loved it.

BUT there is one thing very important which is missing — WHO is the artist? Those drawings are lovely.

Thank you for this wonderful, necessary article. And how wonderful that it was illustrated by Matt Patterson’s stunning illustrations, which always reveal his devotion to these creatures!

Their website: https://turtlerescueleague.org/

D CEDAR the artist is Matt Patterson, truly amazing artwork and a great person. http://www.mpattersonart.com

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.