Close your eyes: What do you see? Of the world you know, what pulses beneath? What does it take to see through words like veils, images like mirages? Close your eyes.

I. Attention

To look is an act of choice. Choosing what is observed becomes a political act for someone like myself. Choosing not to see becomes a privilege only the privileged can afford.

—Helena María Viramontes

Crisp, early-September air greets me as I exit the airport and swing into the car: I’ve arrived in Seattle. My driver, Abdel, relishes the opportunity to welcome a new visitor. He points out the sights we pass at each freeway exit: Japanese Gardens. Pike Place. The reflecting pool. As we wind through downtown, he gestures toward the side of the road. “Last year I gave up eating chicken—and eggs,” he tells me. I look around, wondering how this fits into the improvised tour.

“Driving downtown I saw this truck filled with birds. You could see them—each one—through the openings in the back of the transporter. The birds were stacked from the bottom of the bed to the top, hauled down this highway in the cold, November rain. Living corpses in cages. Exposed. Terrified…” Abdel trails off for a moment and I wonder, is he talking about the birds or himself? Sometimes when we look, the world becomes our mirror, and we can see ourselves in everything.

“I decided that day I would never eat chicken again. My friends have cookouts, and I don’t ever eat that meat. Never again. Not after what I saw here.” He says, gesturing to the stretch of highway that he cannot unsee. I turn toward the empty lane to the right where a livestock transporter filled with birds is all I can see.

Attention matters. The form of attention and quality of presence affects what we see. When we move quickly through the world, the view around us blurs. Therefore, stillness is an essential practice for seeing. To perceive the invisible, we must slow down and cultivate an open presence that allows for anything to enter our view.

The language of visibility implies sightedness; yet, the ability to see is merely one form of perception. Blindness does not constrict perception of the world nor place any limitations upon visioning of what may be. The experience of the world for sighted people is influenced by the physiology of eyesight. Sight, like any of our senses, serves as one pathway for experiencing what is and effecting what may be. The ability to see is what we make of it. “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; What is essential is invisible to the eye,” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry famously wrote.

Close your eyes: What do you see?

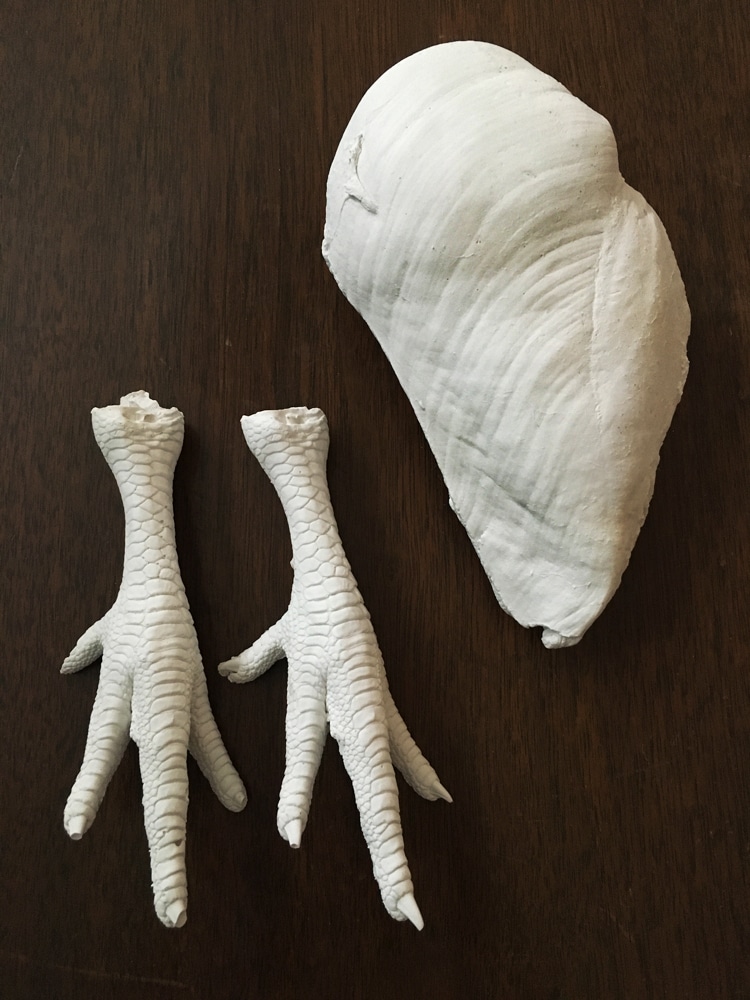

Chickens’ Wings, 2021, plaster casts

Wings and Bones, 2021, plaster casts

II. Witness

The opposite of a witness is a spectator. —Elie Wiesel

When you live a subsistence lifestyle in Southeast Alaska, a summer day sends you spinning from dawn to dusk: food to harvest, fish to catch, fuel to gather, and all the while, wildlife to watch. On a damp August day, Jed left his cabin to begin the bustle of subsistence business. As he walked past his garden, he noticed an iridescent green lump in one of his flower pots. In the afternoon, he passed by it again and recognized the form of a hummingbird in a state of torpor. He knelt on the ground and scooped up the delicate bird’s body.

Inside his home, warmth began to wake the bird from her survival state. He extended his finger, offering her some sugar water, which she licked off. She slurped the sweet sustenance until she was strong enough to ripple her wings and eventually return back to her buzzing, bird self. Jed released her out into the open where the luminescence of her wings shone bright through the misty afternoon air.

The next day, while taking a break, Jed was surprised by a hummingbird who buzzed around him several times and landed on his shoulder where she proceeded to coo softly into his ear. “Real life is more magical than anything you can make up,” explorer Sylvia Earle once told me. You discover this when you direct your attention to the places where no one has looked. Earle, the woman who plunged into the ocean’s deepest depths and whose voice has risen as witness to what few humans have been able to see, knows something about magic and what witnessing requires.

The bird that Jed saved returned his expression of attention and care. She knew what human kindness looked like and Jed understood hummingbird gratitude. They sat together in an exchange greater than words.

When my friend Jed turned his attention toward this one dying hummingbird, he had watched hundreds of these birds flit through his garden. But this time when he saw, he witnessed. Witnessing created a pathway for love; not the love we humans often wrestle within fantasy or philosophy but the love that grants each of us life. The exchange we participate in as breathing beings with beating hearts.

Becoming a witness requires a form of heart-engaged attention, presence. When our hearts remain closed, we have a tendency to look past or away. We miss the invisible. Astronomer Jill Tarter instructs, “We need to stop projecting what we think onto what we don’t yet know.” Our impulses to understand and fears of the unknown often obstruct the process of witnessing. What we do not see also depends upon where we are looking from. What defines our sightlines? Witnessing may require that we change our vantage point.

As Jed and the hummingbird illustrate, the choice to witness is an act of engagement that opens the way for care. We cannot carry an attitude of indifference about what we witness. When you choose to participate as a witness, love may beckon you into relationship with the previously unseen. Witnessing is work of relationship and reciprocity. Ultimately, to witness widens our world and strengthens our hearts.

Head and heart: In our original state, embryonic, this dichotomy exists only in anticipation. Our bodies tell this story as we develop in the watery world of womb. Head and heart form together from the same cellular layer, unique from the rest of the body, in connection with structures like the larynx that gave rise to language. As anatomist Frank Willard has described, this cellular layer, the same cells responsible for the gill slits and oxygen exchange of our distant ancestors, allowed for the development of the bulbous language center of human brains along with the language structures that produced the ability to phonate: in a very real way, the wording of the world began with breath.

Close your eyes: Take a breath.

Chicken Feet, Chicken Breast, 2020, plaster casts

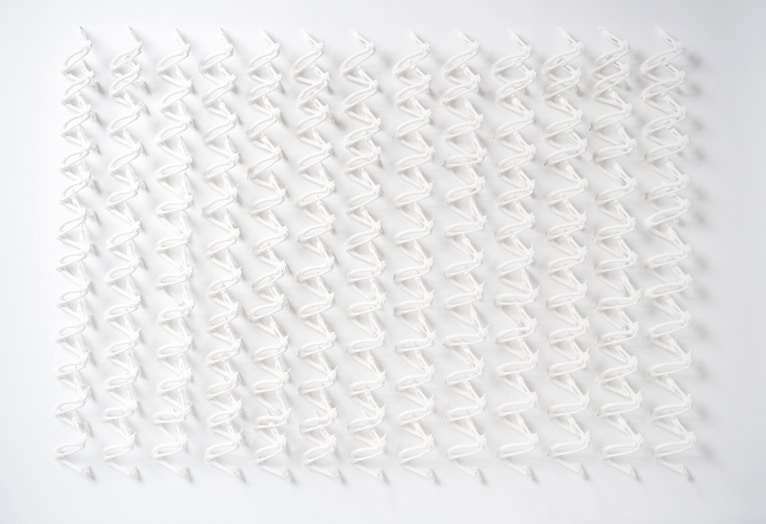

Wing Bones Woven, 2021, plaster casts

III. Vision

And the tragedy is, so often these forty million people [living in poverty] are invisible because America is so affluent, so rich. Because our expressways carry us from the ghetto, we don’t see the poor…we are coming [to Washington] to engage in dramatic nonviolent action, to call attention to the gulf between promise and fulfillment; to make the invisible visible.

—Martin Luther King, Jr.

The words we utter shape the world we see. “It wasn’t just the regular folks.” The phrase that became a national conversation in the United States when Wisconsin Supreme Court Chief Justice Patience Roggensack attributed a local surge in coronavirus cases to meatpacking workers: “That’s where Brown County got the flare. It wasn’t just the regular folks in Brown County.” From these words, a picture formed of the meatpacking workers, a group including many Black and brown people, as separate from their community, as other.

What’s invisible and what is made to be invisible? The rigidity of systems of oppression and ways of separation increases with phrases, whether expressed intentionally or not, like Roggensack’s; phrases repeated in news, set into policy, engraved on buildings, and ultimately written as history. If we are to one day make the invisible visible, we have a responsibility for the ways we word our world, how we employ that channel between our heads and our hearts.

Writing is an act of visibility. Yet, every spotlight we shine casts a shadow somewhere else. While I ask you to attend to this question of what makes the invisible visible, I must accept that even this exploration renders something unseen. As poet Jamaal May said: “Language is both a key and a cage.”

And yet, if we look with the heart—if we can find our way toward a practice of living as witnesses—we may unlock the cages between us. Separation’s strength is in its rigidity; in softening ourselves and opening our hearts to the individual and particular, to each other and all breathing beings, the systems surrounding us may melt and meld into something we have not yet seen.

What makes the invisible visible?

Open your eyes: What will you witness?

Plaster casts, 2-channel projection, plywood, installation view

Invisible Visible explores relationships between systems rendered invisible that exist all around us. A multi-disciplinary project including sculpture and video installation, photography, and writings, created as an act of acknowledgment for the many lives involved in factory farming: the chickens and the workers, together subjected to the suffering created by our industrial food system.

Katherine Kassouf Cummings is a Lebanese-American writer born to and living on the ancestral homelands of the people of the Council of Three Fires (Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa) as well as the Menominee, Miami, and Ho-Chunk nations. She is co-editor of the book What Kind of Ancestor Do You Want to Be? She serves as Managing Editor at the Center for Humans and Nature, where she leads the Questions for a Resilient Future and the Editorial Fellows program.

Colleen Plumb makes photographs, videos, and installations that look at the complex and contradictory relationships humans have with nonhuman animals. Plumb’s work is held in several permanent collections and has been widely published and exhibited. Her 2021 installation, Surveilling Snow Lily, at Roman Susan in Chicago, was highlighted as a must-see in ARTFORUM gallery guide. Plumb’s first photography monograph, Animals Are Outside Today, critically documents humans’ ambivalent dispositions towards animals. Plumb’s recent photography book, Thirty Times a Minute, examines the plight of captive elephants. It was listed as a LensCulture favorite book of 2020, by Eastman Museum curator Lisa Hostetler. Plumb teaches in the photography department at Columbia College Chicago.