AFEW YEARS AGO, while living on the Diné Nation, I first heard a striking proclamation that rang through the community with profound urgency: “Tó éí íín´á!”—“water is life.” I saw these words in bold letterpressed signs, t-shirts, and bright graffiti along roadsides. Diné people raised this cry outside tribal offices in Window Rock, Arizona, and literally chased Senator John McCain, seated inside a moving black suburban, off their land to protect their hold on the Little Colorado River water. Such strong reactions were in response to Senate bill S.2109, also known as the Navajo-Hopi Little Colorado River Water Rights Settlement Act of 2012. This bill proposed that the Navajo and Hopi Nations would waive rights to the Little Colorado River in exchange for the Bureau of Reclamation piping clean drinking water into tribal homes. But why waive their rights? I wondered. Who would benefit? According to the New York Times, “Other parties, including Peabody Coal and two other corporations, want[ed] the water for ranching, farming and coal mining operations.” The corporate interest in the water was not new or surprising, yet it heightened community outrage and protest. Fortunately, the bill was never enacted. As a high-desert community that already lives with natural conditions of water scarcity, Diné people have developed traditional ways of honoring and conserving water. Yet they continue to be beleaguered by threats of contamination, waste, and legislative robbery of what little water they have.

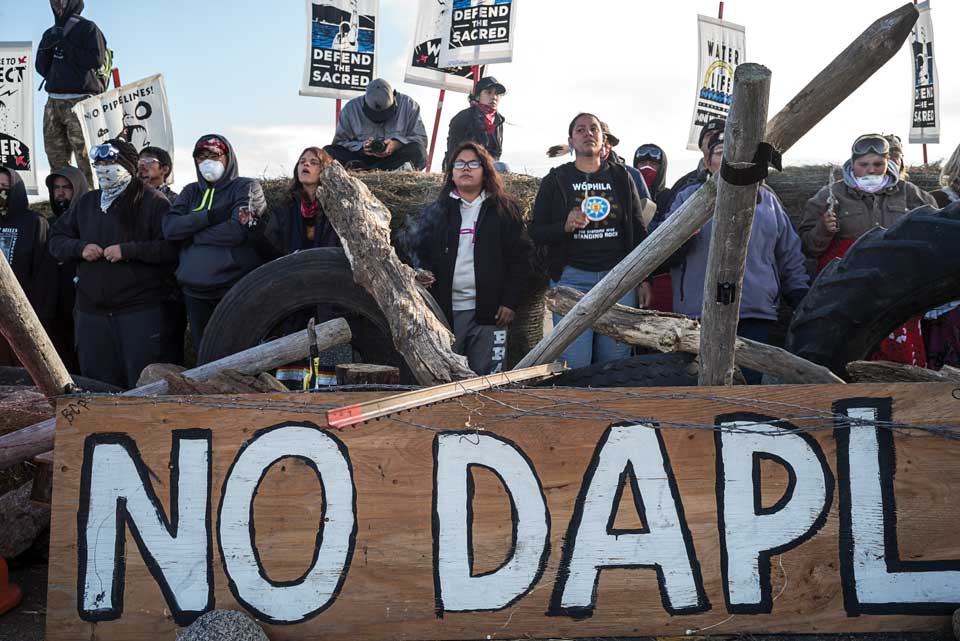

The people of Standing Rock Reservation and their allies have stood solid in prayer to face lines of armed police who used attack dogs, tasers, tear gas, rubber bullets, water cannons, and sonic weaponry to silence this undeniable truth: Mni Wiconi. “Water is life.” Hundreds of US tribes issued statements of support for Standing Rock’s fight to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline from drilling under Lake Oahe in the Missouri River. People from around the world, from the Pacific Islands to the Middle East to Europe, called out in the Lakota language, “Mni Wiconi!” It’s this sensibility that is important to the present: water is not a “resource,” it’s not a “utility,” it’s not negotiable. Rather, “it is sacred.” I have heard these words many times. Without water, there is no life. Simple. True. Resonant, down to our very cells.

Tonight, I spent time rewatching footage of both Diné and Lakota efforts to protect their water. It hurts to watch outright violence by law enforcement and, equally so, the casual dismissal of urgent community voices by onlookers and passers-by. Yet there’s an inimitable strength in the people’s stance that gives me hope. The Diné and Lakota people are not alone, mind you. These battles rage across the nation—in tribal and nontribal communities alike. But I drank in these videos with amazement. I’m reminded that at the center and inception of so many of these movements are the youth—bright, resilient energy. Fire. In concentric circles around them, I see our women. Our men. Elders. Allies. I have considered why I feel devastated by our losses as much as I feel bolstered and empowered. I sometimes think, If ten thousand people camping at Standing Rock to protect the Missouri River could not stop the siege of the Dakota Access Pipeline, then what does it take? What more?

On March 5, 2017, six weeks after the current US president signed an executive memorandum to resume construction of the Dakota Access and the Keystone XL pipelines, the Whitney Museum held an event, “Words for Water.” A gathering of artists, all of whom are Native women, presented written and musical pieces in honor of this land, its water, and the people working to protect it. Artists included Natalie Diaz, Heid Erdrich, Louise Erdrich, Jennifer Elise Foerster, Joy Harjo, Toni Jensen, Deborah A. Miranda, Laura Ortman, and myself. Here, we offer a selection of works shared that night to a room tossed by waves of emotions and questions. I do not have the answer to What more does it take? except to say that I know, we all know, it will take more. And toward this, our work continues.

—Layli Long Soldier

Prayer of Prayers

For the Water Protectors at Standing Rock

The leaves hang on

into mid-November

oak, alder, locust—

each one a prayer flag

singing aloud—

scarlet, cinnamon, gold

rippling with

wind’s rough caress.

Every acorn,

every hickory nut,

a tobacco tie

hung in the trees;

they call out to us

come harvest your prayers.

Soon a blanket of prayers

will cover the earth

and the trees will stand

like prayer poles

dressed in feathers—

gifts from blue jay,

eagle, hummingbird,

meadowlark.

The planet prays for us,

for itself;

the planet sings

for November’s endurance,

weaves a nest

for our future

to curl up inside

and learn winter’s

Kevlar-wrapped stories.

This planet is a prayer.

Each icy night

under floodlights

and water cannons

she offers up moon

and stars, a holiness of cold.

You think prayer

cannot change this war?

Then redefine prayer:

it is clothing frozen

to the bodies of warriors

who do not carry

any other weapon

against water cannons;

it is eyes swollen shut

with tear gas, a relative

holding a bottle of saline solution;

it is the ferocious flower

left behind by a rubber bullet

blossoming on the face

of a woman

who is, in the end,

made wholly of prayer,

her spirit an impenetrable vessel

carrying prayer out to the edges

of camp where armed officers

try to hold prayer at bay,

as if prayer were a rabid bear

or a pack of wolves

that must be isolated,

beaten, eradicated

because prayer is contagious

prayer is that dangerous

prayer rages like a bonfire

no fire hose can quench.

The leaves hang on

into mid-November

oak, alder, locust—

each one a prayer flag

howling hoarse—

scarlet, cinnamon, gold

snapping under

wind’s cracked hands.

Every acorn,

every hickory nut,

a tobacco tie

swaying in the trees;

they cry out to us

come harvest your prayers

come pound them into meal

come mix them with river water

come cook them on this blazing rock:

oh people, come feast

on this prayer so righteous

it burns your tongues;

wash it down

with a sip from the river

whose songs will always call you

Beloved.

—Deborah A. Miranda

Women in the Fracklands

On Water, Land, Bodies, and Standing Rock

By Toni Jensen

I.

On Magpie Road, the colors are in riot. Sharp blue sky over green and yellow tall grass that rises and falls like water in the North Dakota wind. Magpie Road holds no magpies, only robins and partridge and crows. A group of magpies is called a tiding, a gulp, a murder, a charm. When the men in the pickup make their first pass, there on the road, you are photographing the grass against sky, an ordinary bird blurring over a lone rock formation.

You do not photograph the men, but if you had, you might have titled it “Father and Son Go Hunting.” They wear camouflage, and their mouths move in animation or argument. They have their windows down, as you have left those in your own car down the road.

Magpie Road lies in the middle of the 1,028,051 acres that make up the Little Missouri National Grasslands in western North Dakota. Magpie Road lies about two hundred miles north and west of the Standing Rock Reservation, where thousands of indigenous people and their allies came together to protect the water, where sheriff’s men and pipeline men and National Guardsmen donned their riot gear, where those men still wait, where they still hold tight to their riot gear.

If a man wears his riot gear during prayer, will the sacred forsake him? If a man wears his riot gear to the holiday meal, how will he eat? If a man enters the bedroom in his riot gear, how will he make love to his wife? If a man wears his riot gear to tuck in his children, what will they dream?

Magpie Road is part of the Bakken, a shale formation lying deep under the birds, the men in the truck, you, this road. The Bakken is what is known as a marine shale—meaning, once, here, instead of endless grass lay endless water. You left Standing Rock for the Bakken, and the woodsmoke from the water–protector camps still clings to your hair.

There, just off Magpie Road, robins sit on branches or peck the ground. A group of robins is called a riot. This seems wrong at every level except the taxonomic. Robins are ordinary, everyday, general-public sorts of birds. They seem the least likely of all birds to riot.

In the Bakken and in all fracklands towns, the influx of men, of workers’ bodies, bring an overflow of crime. In the Bakken at the height of the oil and gas boom, violent crime, for example, increased by 125 percent. North Dakota attorney general Wayne Stenehjem called this increase in violent crime “disturbing” and cited aggravated assaults, rapes, and human trafficking as “chief concerns.”

When the men in the truck make their second pass, there on the road, the partridge sit in their nests, and the robins are not in formation. They are singular. No one riots but the colors. The truck revs and slows and revs and slows beside you. You have taken your last photograph of the grass, have moved yourself back to your car. The truck pulls itself close to your car, revving parallel.

You are keeping your face still, starting the car. You have mislabeled your imaginary photograph. These men, they are not father and son. At close range, you can see there is not enough distance in age. One does sport camouflage, but the other, a button-down shirt, complete with pipeline logo over the breast pocket. They are not bird hunters. The one in the button-down motions to you out the window with his handgun, and he smiles and says things that are incongruous with his smiling face.

II.

In the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania, a floorhand shuts the door to his hotel room, puts his body between the door and a woman holding fresh towels. A floorhand is responsible for the overall maintenance of a rig. The woman says to you that he says to her, “I just want some company.” He says it over and over, into her ear, her hair, while he holds her down. She says it to you, your ear, your hair. She hates that word now, she says, company. A floorhand is responsible for the overall maintenance of a rig. A floorhand is responsible.

But who is responsible for and to this woman, her safety, her body, her memory? Who is responsible to and for the language, the words that will not take their leave?

In a hotel in Texas, in the Permian Basin, you call the front desk and report on the roughneck in the room upstairs. You dial zero while he hits his wife/girlfriend/girl he has just bought. You dial zero while he throws her and picks her up and starts again. Or at least, one floor down, this is the soundtrack. Upon his departure, the man uses his fist on every door down your hall. The sound is loud but also is like knocking, like Hello, like Anybody home? You wonder if he went first to the floor above but think not. Sound, like so many things, operates mostly through a downward trajectory.

At a hotel where South Dakota and Wyoming meet, you are sure you have driven out of the Bakken, past its edge, far enough. That highway that night belongs to the deer, and all forty or fifty of them stay roadside as you pass. You arrive at the hotel on caffeine and luck. The parking lot reveals your calculus to have been a mistake—frack truck after pickup after frack truck.

Two roughnecks stagger into your line of sight, one drunk, the other holding up the first while he zips his fly. This terminology, fly, comes from England, where it first referred to the flap on a tent—as in, Tie down your tent fly against the high winds. As in, Don’t step on the partridge nest as you tie down your fly. As in, Stake down your tent fly against the winter snow, against the rubber bullets, against the sight of the riot gear.

The men sway across the lot, drunk loud, and one says to the other, “Hey, look at that,” and you are the only that there. When the other replies, “No. I like the one in my room just fine,” you are sorry and grateful for the one in an unequal measure.

You cannot risk more roadside deer, and so despite all your wishes, you stay the night. A group of deer is called a herd; a group of roe deer, a bevy. There is a bevy of roe deer in the Red Forest near Chernobyl. The Bakken is not Chernobyl because this is America. The Bakken is not Chernobyl because the Bakken is not the site of an accident. The Bakken is not Chernobyl because the Bakken is no accident.

III.

On Magpie Road, the ditch is shallow but full of tall grass. With one hand, the button-down man steers his truck closer to your car, and with the other, he waves the handgun. He continues talking, talking, talking. The waving gesture is casual, like the fist knocking down the hotel hallway—Hello, anyone home, hello?

Once on a gravel road, your father taught you to drive your way out of a worse ditch. When the truck reverses, then swerves forward, as if to block you in, you take the ditch to the right, and when the truck slams to a stop and begins to reverse at a slant, taking the whole road, you cross the road to the far ditch, which is shallow, is like a small road made of grass, a road made for you, and you drive like that, on the green and yellow grass until the truck has made its turn, is behind you. By then you can see the highway, and the truck is beside you on the dirt road, and the truck turns right, sharp across your path. So you brake then veer left. You veer out, onto the highway, fast, in the opposite direction.

Left is the direction to Williston. So you drive to Williston, and no one follows.

At a big–box store in Williston, a lot sign advertises overnight parking for RV’s. You have heard about this, how girls are traded here. You had been heading here to see it, and now you’re seeing it. Mostly, you’re not seeing. You are in Williston for thirty-eight minutes, and you don’t leave your car.

You spend those thirty-eight minutes driving around the question of violence, of proximity and approximation. How many close calls constitute a violence? How much brush can a body take before it becomes a violence, before it makes violence, or before it is remade—before it becomes something other than the body it was once, before it becomes a past-tense body?

IV.

At Standing Rock, the days pass in rhythm. You sort box upon box of donation blankets and clothes. You walk a group of children from one camp to another so they can attend school.

The night before the first walk, it has rained hard and the dirt of the road has shifted to mud. The dirt or mud road runs alongside a field, which sits alongside the Cannonball River, which sits alongside and empties itself into the Missouri.

Over the field, a hawk rides a thermal, practicing efficiency.

After school but before the return walk, the children and you gather with hundreds to listen to the tribal chairman, to sit with elders to pray, to talk of peace.

That afternoon, you walk the children home from school, there on the road. You cross the highway, the bridge, which lies due south of the Backwater Bridge of the water cannons or hoses. But this bridge, this day, holds a better view. The canoes have arrived from the Northwest tribes, the Salish tribes. They gather below the bridge on the water, and cars slow alongside you to honk and wave. Through their windows, people offer real smiles.

That night, under the stars, firelit, the women from the Salish tribes dance and sing.

Winter Watch

—Cannonball River, November 2016

We committed ourselves to the prairie,

bees without a queen, swarming frozen ground.

Our hours lifted their lacy black veils—

a procession of grieving women.

Broke, we talked of wilderness

and failure, time’s sentient materialism,

the clock without hands now, without its tick—

awoke, snow-covered, in a dead meadow.

Watching the sunrise rake across stones

I think about stories superimposed,

all these bodies passing through each other.

Startled, a doe slips into fog—a fugue

blows my shadow to the other side of grief.

We sort more piles of things—no answer.

Fresh hay for horse feed; tipi poles; propane.

Hours like dull gold blow across the prairie.

Oatmeal, canned beans. Garlic salt, hominy.

White, brown, or wild rice.

Rock salt. Flour.

A queen travels to the inner reaches

alone, by foot, lanterns clicking through grass.

Brightness for a moment, until time

returns, and I remember who I am,

how crowded this terminal of the world—

deer gutted at the mudbank,

hoofprints trailing into winter wheat.

—Jennifer Elise Foerster

Anaamiindim In the Depths of a Body of Water

Bakobiikawe S/he leaves tracks going into the water

Bakobiidaabi’iwe S/he dives into the water

Bakobii S/he goes down into the water

Agwamo S/he floats, still in the water

Mookibii S/he emerges from the water

Gwaaba’ibi S/he draws the water

Biidoobii S/he brings the water

Nibi the water

—Heid Erdrich

The First Water Is the Body

The Colorado River is the most endangered river in the United States—also, it is a part of my body.

I carry a river. It is who I am: ’Aha Makav.

This is not metaphor.

When a Mojave says, Inyech ’Aha Makavch ithuum, we are saying our name. We are telling a story of our existence. The river runs through the middle of my body.

So far, I have said the word river in every stanza. I don’t want to waste water. I must preserve the river in my body.

In future stanzas, I will try to be more conservative.

~

The Spanish called us, Mojave. Colorado, the name they gave our river because it was silt-red-thick.

Natives have been called red forever. I have never met a red native, not even on my reservation, not even at the National Museum of the American Indian, not even at the largest powwow in Parker, Arizona.

I live in the desert along a dammed blue river. The only red people I’ve seen are white tourists sunburned after being out on the water too long.

~

’Aha Makav is the true name of our people, given to us by our Creator who loosed the river from the earth and built it, into our living bodies.

Translated into English, ’Aha Makav means the river runs through the middle of our body, the same way it runs through the middle of our land.

This is a poor translation, like all translations.

In American minds, the logic of this image will lend itself to surrealism or magical realism—

Americans prefer a magical red Indian, or a shaman, or a fake Indian in a red dress, over a real native. Even a real native carrying the dangerous and heavy blues of a river in her body.

What threatens white people is often dismissed as myth.

I have never been true in America. America is my myth.

~

Derrida says, Every text remains in mourning until it is translated.

When Mojaves say the word for tears, we return to our word for river, as if our river were flowing from our eyes. A great weeping, is how you might translate it. Or, a river of grief.

But who is this translation for? And will they come to my language’s four-night funeral to grieve what has been lost in my efforts at translation? When they have drunk dry my river will they join the mourning procession across our bleached desert?

The word for drought is different across many languages and lands.

The ache of thirst, though, translates to all bodies along the same paths—the tongue and the throat. No matter what language you speak, no matter the color of your skin.

~

We carry the river, its body of water, in our body.

I do not mean to imply a visual relationship. Such as: a native woman on her knees holding a box of Land O’Lakes butter whose label has a picture of a native woman on her knees holding a box of Land O’Lakes butter whose label has a picture of a native woman on her knees . . .

We carry the river, its body of water, in our body. I do not mean to invoke the Droste effect.

I mean river as a verb. A happening. It is moving within me right now.

~

This is not juxtaposition. Body and water are not two unlike things—they are more than close together or side by side. They are same—body, being, energy, prayer, current, motion, medicine.

This knowing comes from acknowledging the human body has more than six senses. The body is beyond six senses. Is sensual. Is always an ecstatic state of energy, is always on the verge of praying, or entering any river of movement.

Energy is a moving like a river moving my moving body.

~

In Mojave thinking, body and land are the same. The words are separated only by letters: ’iimat for body,’amat for land. In conversation, we often use a shortened form for each: mat-. Unless you know the context of a conversation, you might not know if we are speaking about our body or our land. You might not know which has been injured, which is remembering, which is alive, which was dreamed, which needs care, which has vanished.

If I say, My river is disappearing, do I also mean, My people are disappearing?

~

How can I translate—not in words but in belief—that a river is a body, as aliveas you or I, that there can be no life without it?

~

John Berger wrotetrue translation is not a binary affair between two languages but a triangular affair. The third point of the triangle being what lay behind the words of the original text before it was written. True translation demands a return to the pre-verbal.

Between the English translation I offered,and the urgingI felt to first type ’Aha Makav in the lines above, is not the point where this story ends or begins.

We must go to the place before those two points—we must go to the third place that is the river.

We must go to the point of the lance our creator stabbed into the earth, and the first river bursting from that clay body into mine. We must submerge beneath thoseonce warm red waters now channeled-blue and cool, the current’sendless yards ofemerald silk wrapping the body and moving it, swift enough to take life or give it.

We must go until we smell the black-root-wet anchoring the river’smud banks.

~

What is this third point, this place beyond the surface, if not the deep-cut and crooked bone-bed where the Colorado River runs—like a one thousand fourhundred and fifty mile thirst—into and through a body?

Berger called it the pre-verbal.Pre-verbal as in the body when the body was more than body. Before it could name itself body and be limited to the space body indicated.

Pre-verbal is the place where the body was yet a green-blue energy greening, greened, and bluing the stone, the floodwaters, the razorback fish, the beetle, and the cottonwoods’ and willows’ shaded shadows.

Pre-verbal was when the body was more than a body and possible.

One of its possibilities was to hold a river within it.

~

A river is a body of water. It has a foot, an elbow, a mouth. It runs. It lies in a bed. It can make you good.It remembers everything.

~

America is a land of bad math and science: the Right believes Rapture will save them from the violence they are delivering upon the earth and water; the Left believes technology, the same technology wrecking the earth and water, will save them from the wreckage or help them build a new world on Mars.

~

If I was created to hold the Colorado River, to carry its rushing inside me, how can I say who I am if the river is gone?

What does ’Aha Makav mean if the river is emptied to the skeleton of its fish and the miniature sand dunes of its dry silten beds?

If the river is a ghost, am I?

Unsoothablethirst is one type of haunting.

~

A phrase popular or more known to non-natives during the Standing Rock encampment was, Water is the first medicine. It is true.

Where I come fromwe cleanse ourselves in the river. Not like a bath with soap. I mean:the water makes us strong and able to move forward into what is set before us to do with good energy.

We cannot live good, we cannot live at all, without water.

If we poison and use up our water, how will we cleanse ourselves of these sins?

~

To thirst and to drink is how one knows they are alive, and grateful.

To thirst and then not drink is . . .

~

If your builder could place a small red bird in your chest to beat as your heart, is it so hard for you to picture the blue river hurtling inside the slow muscled curves of my long body? Is it too difficult to believe it is as sacred as a breath or a star or a sidewinder or your own mother or your lover?

If I could convince you, would our brown bodies and our blue rivers be more loved and less ruined?

The Whanganui River in New Zealand now has the same legal rights of a human being. In India, the Ganges and Yamuna rivers now have the same legal status of a human being. Slovenia’s constitution now declares access to clean drinking water to be a national human right. While in the US, we are tear-gassing and rubber-bulleting and kenneling natives who are trying to protect their water from pollution and contamination at Standing Rock in North Dakota. We have yet to discover what the effects of lead-contaminated water will be on the children of Flint, Michigan, who have been drinking it for years.

~

We think of our bodies as being all that we are: I am my body. This thinking helps us disrespect water, air, land, one another. But water is not external from our body, our self.

My Elder says: Cut off your ear, and you will live. Cut off your hand, you will live. Cut off your leg, you can still live. Cut off our water: we will not live more than a week.

The water we drink,like the air we breathe,is not a part of our body but is our body. What we do to one—to the body, to the water—we do to the other.

~

Toni Morrison writes, All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.Back to the body of earth, of flesh, back to the mouth, the throat, back to the womb, back to the heart, to its blood, back to our grief, back backback to when we were more than we have lately become.

Will we soon remember from where we’ve come? The water.

And once remembered, will we return to that first water, and in doing so return to ourselves, to each other, better and cleaner?

Do you think the water will forget what we have done, what we continue to do?

—Natalie Diaz

Advice to Myself #2: Resistance

Resist the thought that you may need a savior,

or another special being to walk beside you.

Resist the thought that you are alone.

Resist turning your back on the knife

of the world’s sorrow,

resist turning that knife upon yourself.

Resist your disappearance

into sentimental monikers,

into the violent pattern of corporate logos,

into the mouth of the unholy flower of consumerism.

Resist being consumed.

Resist your disappearance

into anything except

the face you had before you walked up to the podium.

Resist all funding sources but accept all money.

Cut the strings and dismantle the web

that needing money throws over you.

Resist the distractions of excess.

Wear old clothes and avoid chain restaurants.

Resist your genius and your own significance

as declared by others.

Resist all hint of glory but accept the accolade

as tributes to your double.

Walk away in your unpurchased skin.

Resist the millionth purchase and go backward.

Get rid of everything.

If you exist, then you are loved

by existence. What do you need?

A spoon, a blanket, a bowl, a book—

maybe the book you give away.

Resist the need to worry, robbing everything

of immediacy and peace.

Resist traveling except where you want to go.

Resist seeing yourself in others or them in you.

Nothing, everything, is personal.

Resist all pressure to have children

unless you crave the torment of joy.

If you give in to irrationality, then

resist cleaning up the messes your children make.

You are robbing them of small despairs they can fix.

Resist cleaning up after your husband.

It will soon replace having sex with him.

Resist outrageous charts spelling doom.

However you can, rely on sun and wind.

Resist loss of the miraculous

by lowering your standards

for what constitutes a miracle.

It is all a fucking miracle.

Resist your own gift’s power

to tear you away from the simplicity of tears.

Your gift will begin to watch you having your emotions,

so that it can use them in an interesting paragraph,

or to get a laugh.

Resist the blue chair of dreams, the red chair of science, the black chair of the humanities, and just be human.

Resist all chairs.

Be the one sitting on the ground

or perching on the beam overhead

or sleeping beneath the podium.

Resist disappearing from the stage,

unless you can walk straight into the bathroom and resume the face,

the desolate face, the radiant face, the weary face, the face

that has become your own, though all your life

you have resisted it.

—Louise Erdrich

This Morning I Pray for My Enemies

And whom do I call my enemy?

An enemy must be worthy of engagement.

I turn in the direction of the sun and keep walking.

It’s the heart that asks the question, not my furious mind.

The heart is the smaller cousin of the sun.

It sees and knows everything.

It hears the gnashing even as it hears the blessing.

The door to the mind should only open from the heart.

An enemy who gets in, risks the danger of becoming a friend.

—Joy Harjo

Reprinted from Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings by Joy Harjo. Copyright Ó 2015 by Joy Harjo. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Camille Seaman is a photographer whose work focuses on the fragile environments, extreme weather, and stark beauty of the natural world.

Deborah A. Miranda is Esselen and Chumash. She teaches literature and creative writing at Washington and Lee University.

Toni Jensen’s first story collection is From the Hilltop. She teaches at the University of Arkansas.

Jennifer Elise Foerster is the author of Leaving Tulsa. She is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and a PhD candidate at the University of Denver.

Heid Erdrich is a Turtle Mountain Ojibwa author. Her new book is Curator of Ephemera at the New Museum for Archaic Media.

Natalie Diaz is a Mojave and Pima language activist. She grew up at Fort Mojave along the Colorado River.

Louise Erdrich recently won a National Book Critics Circle award for fiction. She is Ojibwe, enrolled at Turtle Mountain.

Joy Harjo’s most recent collection of poetry is the award-winning Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings.

Comments

amazing and relevant. i will save this and read it again, and again.

Profound

So profound

So beautiful, righteous, tragic. Thank you.

I’m Oglala Sioux from Pine Ridge, South Dakota. I live in Ft.Worth, Tx.

I pray daily for ( All ) water protector’s, and continue to feed on all

prayer’s I read.

This fight isn’t over by far.We must protect our water and land from ( All ) whom wish to destroy it.

God Bless our water,and our land.Amen.

I am not indigenous, although I grew up and spent my early adulthood with the Kiowa. I learned so much; I learned history from a different perspective. I miss terribly that I lost touch when “my family” were gone. My greatest hope is that the non-indigenous ones will learn from the first peoples here in time to turn life here a better way, a way that honors what we have been given in the world we have, and will restore the damage the later people coming here have done. And I’m very much afraid that we new-comers will not learn, or will try to learn when it’s too late. I have another side that hopes they will learn early enough. Two years ago my students were asking me for topics for their required presentations, and I ask them if they knew about Standing Rock. I had five students, in different classes, learning about it and becoming more interested to learn more. It was a small beginning, but a beginning.

Absolutely beautiful!

What can I possibly say? The words, tiny boats on waves of many currents – I am carried home,

“A river is a body of water. It has a foot, an elbow, a mouth. It runs. It lies in a bed. It can make you good. It remembers everything.” This is anthropocentric arrogance and sentimentality. Rivers are inanimate natural phenomena. What do they “remember”? Maybe a river can make you good, but why not also bad? Rivers are not saints.

One might also note that the idea that this is ancestral Sioux land is rather shallow. From whom did the Sioux get this land and how? Only a few hundred years ago the Missouri Valley there was dominated by large towns of Mandan and Arikara earth lodges. I don’t want to take sides in the tribal wars, but I did work on the excavation of the Swan Creek earth lodge town where raiders from other tribes burned down a town of some 3,000 people.

Until the US government implements just one – ONE – of the many treaties they made with the indigenous tribes, I for one will have no confidence in their honesty or reliability.

I intend to pass this on to as many people as possible

To Wallace Kaufman

Natalie Diaz does not suggest rivers are like people (anthropocentric arrogance) but rather people are like rivers or each like each other. Or perhaps people, other animals, rivers, trees, grasses all part of the interwoven singular entity – life. A lesson us white guys have a hard time appreciating but need to hurry up and “get it”.

Amazing piece and inspiring selection of writers. Thank you for this.

From Empedocles, to reference a book title, quoted by Edelman, Gerald

By earth, we see earth; by water, water;

by air, bright air, by fire, brilliant fire.

I want to be a river.

True indeed. When water is lost, indeed life is lost.

Unconditional Love

In the US, and in Brazil, as I write, First Nations Peoples are being killed by Covid-19 at a higher rate those who look like the fascist leaders of each nation. It reminds me of blankets infected with colonial diseases. I am afraid it is not an accident.

I can feel this in my bones. So incredibly grateful to these writers. Thank you for sharing.

Stunning reminder that we are water. Without clean, active water, we are but dust.

water is life! such inspiring writers and what a beautiful learning for all of us. I wish everyone has a vision as these writers have.

In the poem, the narrator describes a feeling of disconnection from the world around them, stating that “I was a girl of many and other worlds, / but I was anchored only to my body.” This suggests that the narrator feels as though they do not quite belong in the world, as if they are an outsider looking in.

Later in the poem, the narrator describes a dream in which they are “a fish swimming backwards,” further emphasizing their sense of otherness and alienation. This image suggests that the narrator is moving in a direction opposite to that of the rest of the world, again highlighting their sense of disconnection.

The poem also includes references to the narrator’s Native American heritage, which may contribute to their feelings of being an outsider. For example, they describe being “a Mojave who spoke only English,” suggesting that they feel disconnected from their own cultural heritage and perhaps even from their own identity.

Finally, the poem’s title itself – “The First Body Is Water” – suggests a sense of fluidity and changeability, which may again reflect the narrator’s sense of being different from others and not quite fitting in. The use of the word “first” also implies that there may be other “bodies” to come, further emphasizing the idea of transformation and change.

The issue of Water is beyond all races, cultures and belief. IT IS A BASIC REQUIREMENT FOR LIFE ON EARTH. WITHOUT IT NOTHING EXISTS.

I would love to see and participate in a world wide effort to return the waters of our world to its purity for all people, all animals, all lifeforms in a way that no “company of small interests” can out weight the law of purity.

Companies can take their money they make and return water to it’s purity or loose their access. It is not a “right” to use water for capital gains. It is a temporary access with major limitations. This is the only way.

The Laws of Purity is to sustain all life on our planet.

This is no longer a small local issue as media, companies and other “non-life affirmmers” pretend it is.

Lets take this to a level it needs to be addressed. Small gets buried in slander. This is Life and the need for Water to take its rightful place within our burgeoning world, we must define these issues in a concise scientific, and life-affirming manner for the world.

Thank you all who worked so hard at Standing Rock and all the many world wide battles to keep water safe for our offspring.

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.