In 2010, as Myanmar’s military junta prepared to transition to a parliamentary system, it auctioned off 80 percent of the country’s state-owned assets, including many historic buildings in the city of Yangon. A year later, writer and photographer Elizabeth Rush visited Yangon, where she shot more than 2,000 photographs and conducted hundreds of interviews— all before the city’s landscape was changed forever. The result is Still Lifes from a Vanishing City, a book of photographs and essays just out from Things Asian Press.

What’s your connection to this story? What made you want to document Yangon before its transformation?

I lived for a while in Hanoi, Vietnam, and I remember reading an article in a small Thai newspaper that said that the Junta was selling off Myanmar’s state-owned assets in closed-door auctions as the country prepared for its first democratic elections in decades. I knew, instantly, that downtown Yangon was destined to change. Downtown Yangon had the most intact colonial capital in all of the South East, but it wasn’t the architecture that attracted me to it so much as the lives lead within that architecture.

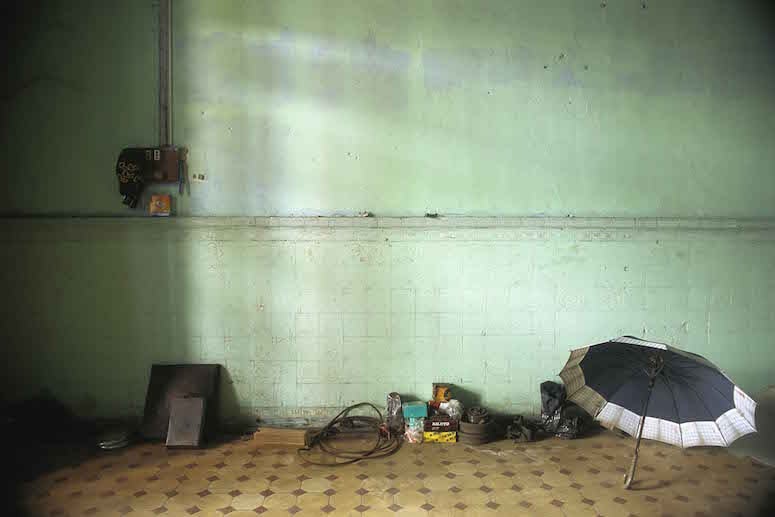

When the military took control in the 1960s, foreign investment pretty much ceased as they implemented a socialist system. They took ownership over much of the property in downtown Yangon, and when they took over the colonial gems they subdivided them and moved in all different races and classes of people to try to create a unified Burmese identity. Which meant that you had street sellers living alongside lawyers in these once-regal buildings. A remarkably egalitarian city emerged, and that was what I loved about Yangon, and I figured the character of that city would be lost as the buildings were auctioned and redeveloped.

Soon after I arrived in Yangon, I was able to get a clandestine list of the auction sites through a Burmese reporter friend. The list was of course written in Burmese, so I had a different person translate it and off I went. I walked every single street in downtown Yangon, trying to identify which of the buildings on the list were residential. Once I knew which buildings were colonial-era and residential I started knocking on doors and asking residents if I could photograph their living rooms. Much to my surprise, pretty much everyone let me in. In many cases I was cooked for and treated like a long-lost friend.

What did it feel like to move through a place that was on the verge of such dramatic change? How did residents seem to feel about the upheaval?

That is a complicated question. There were a lot of extraordinary things taking place while I was in Yangon. I was in Yangon the day that President Thein Sein first released political prisoners, and the reaction was extraordinary. I don’t think I have ever felt a joy quite so profound and on such a large scale in my entire life. I was also there for the first Buddhist holiday—the Festival of Lights—and it was the first time in over a decade that residents were allowed to gather in the street in groups larger than six. No one could believe it. The elation was palpable. I even saw people getting tattoos to commemorate the event. It was one of the best nights of my life.

That said, about half of the people who I worked with knew that they were on the brink of losing their homes. And those that did know were really quite sad and sentimental. It is understandable—they were losing not just the physical structures that sheltered but also some of their memories. But I returned to every home that I photographed with a physical copy of the image that I took, and residents were so happy to receive them as they helped them to remember.

In some cases, though, I returned and the home had already been demolished and the people were gone. In many ways I think I was trying to document what was being lost, and by whom, as the country transitioned to a parliamentary system.

Are there any stories or images that didn’t make it into the book that you’d like to share?

So many. I was often followed by secret police. I had what we call “a minder,” or a person assigned specifically to watch me. When my minder got the sense that I had seen him, he would often drop back and take off his hat, as if that was enough to fool me! It was both funny and frightening. When I had my minder with me I did not interview anyone. I just walked and looked and stopped at street stands for milk tea. It was really a gift to get to spend two years on and off walking the streets of Yangon, getting to know its residents.

I had a Burmese monk friend who advised me, before starting this project, to simply walk into it with a kind and open heart, and I took that advice very seriously. I think that we are taught to live in fear in general, especially when visiting a foreign place, and even more so when visiting a place like Myanmar that has gotten basically only bad press. This project really demanded that I put myself at the mercy of complete strangers and vice versa. And the results were so heartening: I passed so many wonderful mornings in complete strangers’ homes. I wish that I could share the simple joy of those mornings, sipping tea, getting to know a new person whom I knew nothing of before knocking on her door. The lives that everyday people lead in these contentious countries are in no way chronicled in the twenty-four-hour news cycle, and I wanted to draw my readers’ attention to those hidden stories.

Did you learn anything surprising via the taking of these photographs? What emerged for you that you didn’t expect to find?

Ha! I think I might have veered into this question with my last answer, but let’s see. I asked every person I interviewed if they thought about the colonial history of their building and home, and, much to my surprise, the answer was a pretty resounding “no.” Sometimes, someone would say something like, “oh, yes, this building is nice and cool because of the thick colonial-era brick walls,” and then go back to describing whatever important life event took place in the living room. That surprised me: I thought, for all the British may have stolen from Myanmar, perhaps an unmediated experience of the present wasn’t on the list.

What does the new Yangon look like, and what kind of future does it likely hold for its people?

I’ve not been back since concluding my work on this book. Sometimes I receive e-mails from old friends telling me of the demolition of a certain building that I had grown to love. Other times I receive news that one of the buildings I photographed has been put on a heritage list, which makes it illegal to knock down. They say the prices in Yangon are currently equal to Bangkok, which sounds crazy, but I believe it. Yangon is such a beautiful city and for so long it was held at an arm’s distance from the world.

The good news is that there is certainly a growing preservation movement around downtown Yangon. The Yangon Heritage Trust—run by the fantastic writer Thant Myint U—has been doing great work to preserve both the buildings of downtown Yangon and also the truly unique and equitable nature of the city’s character. My publisher has offered to send me back so I can do a follow up book, so hopefully I will make it to Yangon again soon. I miss so much about the city: the smell of jasmine, my fantastic friends and the friendliness of the Burmese, mohinga soup. The list is endless.

Elizabeth Rush’s essay “Elegant Remains,” an account of a canoe trip through New York City’s largest landfill, appeared in the September/October 2014 issue of Orion.

Comments

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.