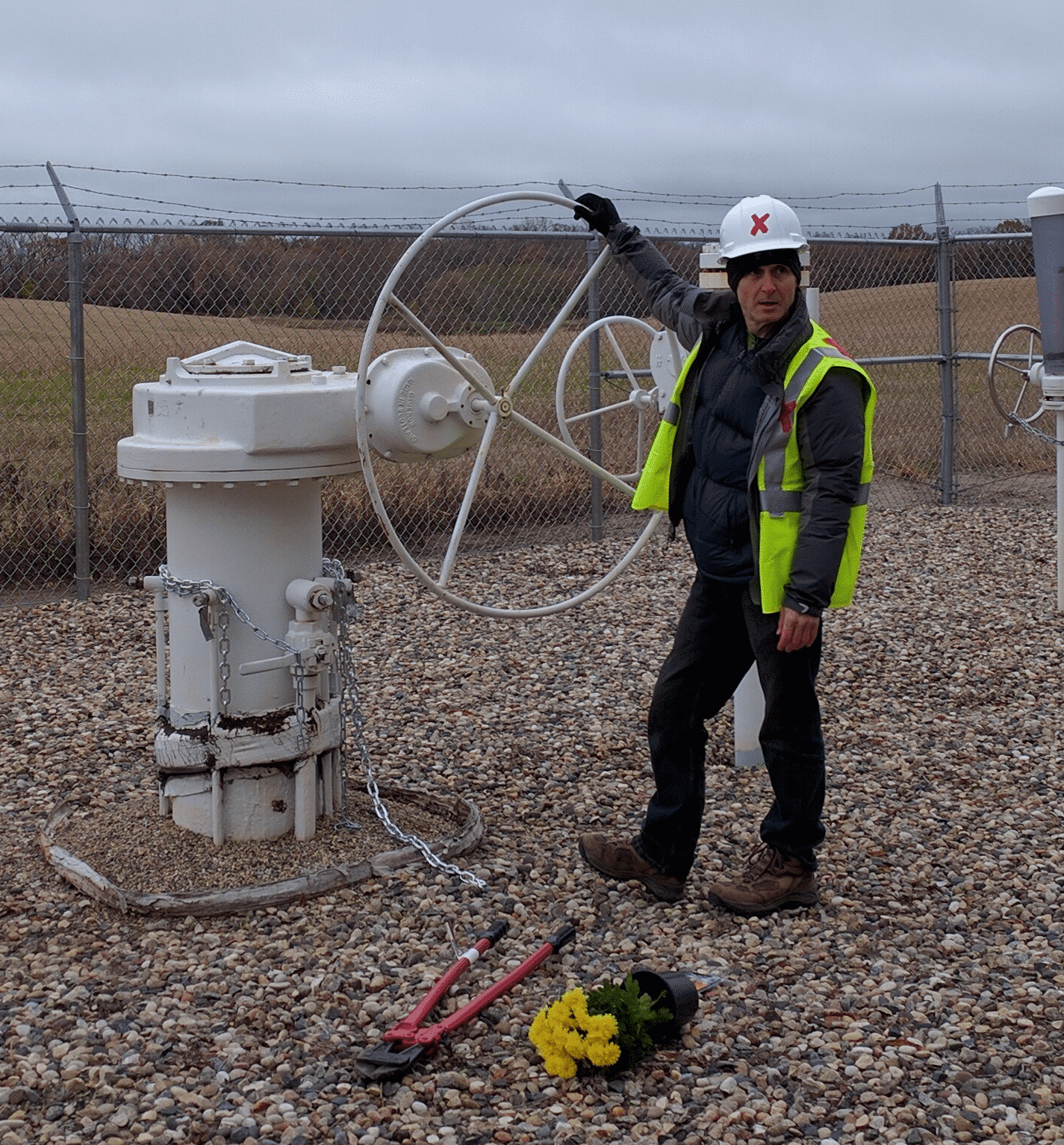

The morning of October 11, 2016, was chilly on the northern plains. Low sun glinted on prairie grasses and on the emergency turn-off valves of the five pipelines that burrowed from Canadian tar-sands oil fields into Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana, and Washington. At 8:30 a.m., people wearing hard hats and yellow safety vests approached each of the pipelines. With bolt cutters, they let themselves into hurricane-fence enclosures. In several locations, one person videotaped the action while another cut the chains that immobilized the valves. These people, men and women, were not burly roustabouts; several were decades past middle age. It took all the strength they had to crank the heavy wheels on the valves. But when they had closed the valves on all five pipelines, the entire flow of crude oil from Canadian tar sands came to a stop.

The shutdown was an act of moral necessity, the Valve Turners explained. Global warming caused by burning fossil fuels is a desperate emergency, so shutting the emergency valves was exactly the right response—an act of sanity in a dangerously surreal world.

Not only that, it was also a call to conscience against an industry that has shown itself willing, for the sake of enormous profit, to take down the natural systems that support life on Earth. Those five pipelines carry 2.9 million gallons of crude each day. This amounts to 15 percent of US daily fossil fuel consumption—as it happens, about the percentage by which fossil fuel use must be reduced each year in order to prevent runaway climate catastrophe.

The action was “the biggest coordinated move on US energy infrastructure ever undertaken by environmental protesters,” Reuters News Agency said, an action that “shook the North American energy industry.”

And what did the state district attorneys call it? Burglary. Violation of the Act for the Suppression of Sabotage and Anarchism. Criminal Trespass. Felony Property Damage. Damaging Critical Public Service Facilities. Felony Criminal Mischief. Trespass and Aiding and Abetting Trespass.

As they awaited trial on these charges, the Valve Turners spoke openly about their reasons for acting. Last winter, I interviewed them in a broadcast webinar and then met them and interviewed them again when they spoke in my hometown of Corvallis, Oregon.

To my surprise, they looked just like the people I meet all the time in the grocery store, carefully choosing apples or dropping carrots in a bag. Again to my surprise—did I expect them to stomp and rant?—they spoke with a quiet passion seldom encountered, engaging with serious questions about what it means to be a good person when the planet and the future are desperately threatened.

I have always believed that the world creates the heroes it needs from the ordinary people who present themselves. Does the world create also the thinkers it needs, from ordinary people who realize that, as the planet’s life-supporting systems approach irredeemable destruction, we are called to think far differently about who we are and what the world asks of us?

The enormity of the world’s crisis is not just sad, but tragic in a classical sense. If plants and animals continue to be driven to extinction at a rate and with a fury the planet has not seen since an asteroid wiped out most dinosaurs, if entire ecosystems fray and fall apart, if savage weather drives people to starvation, to violence, to helpless upheaval and flight—this is unbearably sad. It becomes tragic, however, when those events are the consequences of human decisions rooted in what we might have called virtues: industry, hard work, supreme cleverness and magnificent technological genius, competitive nature, powerful oratory, loyalty to one’s own.

But humans have the capacity—and perhaps one last chance—to make different decisions. As a philosopher—but also as an activist—I wanted to know exactly what the Valve Turners were thinking about that last chance as they waited for sheriffs to drive miles across the prairies to arrest them. What grief and love—or was it fear?—called them to think differently about their obligations? I wanted to know what different set of virtues they called on as they cranked the stiff wheels of the fossil fuel industry. And what might their decisions suggest to the rest of us—heartbroken and desperate to act—about how to answer the world’s urgent call for a new understanding of who we are when we are at our best, we human beings, and how we ought to act?

What did I find when I listened closely to the Valve Turners? Woven together, their words created a new story about the characteristics we will need as we face the global emergencies: Sanity. Prudence. Courage. Good faith. Truth. Compassion. Hope. Integrity.

Sanity

Kathleen: When you describe the world we are living in, you use words like “bizarre,” “surreal,” “terrifying,” “insane.” What are you talking about?

Leonard: Our country has known for decades that a steady, job-preserving shift away from fossil fuels to renewables was necessary. Instead, political and business leaders allowed that opportunity for an easy changeover to slip through our fingers. They are working together instead to prolong fossil fuel profits even though the pollution from extraction, shipment, and burning of those fuels is literally killing us. It’s insane.

Emily: We’ve run out of time, and there is not a single law or legislative proposal on the table anywhere that will keep the earth below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming—beyond which, scientists have made clear, the life-supporting systems that we depend on start to fall apart.

In existing mines and wells alone, there are already three times as much carbon as we can burn and have even a fifty-fifty chance of keeping temperature increases below 1.5 degrees Celsius. We need to immediately end the extraction and burning of the dirtiest fuels—coal and tar sands—in order to preserve a fifty-fifty chance of a livable world. It’s surreal.

We have a choice between a world that is radically changing and inhuman and inhumane, or a world that’s a decent place to live, where people are doing all they can to address the immediate problem of fossil fuels and their tragedies: mass migration and refugees fleeing starvation and unbearable heat and ruined land; widespread extinctions; acidic oceans that may not produce enough oxygen for whales—or for us. I’m not fighting fossil fuels because I want it to be a little less hot and have there be a handful fewer people suffering and a handful fewer species going extinct.

Prudence

Kathleen: Enbridge Inc, the owner of two of these pipelines, said that you were “inviting an environmental incident,” adding, “These are criminal acts that endanger the public and the environment. We take this very seriously.” The Montana Petroleum Association called you “ecoterrorists,” which is harsh indeed. How do you respond?

Michael: The only property damage I caused was to two small padlocks that I snapped with bolt cutters. I replaced one, so I owe them one. Fine.

Ken: As Bill McKibben has said for years, the real radicals are running the fossil fuel companies—apparently they think it’s okay to play dice with every life on the planet.

Emily: I would say three things. One, we shut off the emergency shut-off valves! The only reason they exist is so that if there’s a fire or something else going on, local emergency personnel can shut them down. So if it’s true that shutting them down endangers the environment, that’s a little disturbing.

Two, between 1999 and 2010, Enbridge had 804 spills, one every five days. It’s not shutting down the pipelines that’s dangerous; it’s running them.

And three, there is a 100 percent chance of catastrophe if we do not shut down the tar-sands extraction, as global warming irretrievably damages the life-supporting systems of the planet. That sounds like “inviting an environmental incident” for sure.

Michael: But in another respect, what we did was very dangerous for the oil industry, because we revealed how vulnerable it is. There was a question in the White House briefing room the day after this action about the security of our nation’s oil supply. They know that they can only do this right under our noses with our consent.

Emily: That’s something I think is super important. Whether it’s tankers or trucks or pipelines, these companies can’t destroy life on Earth without our implicit permission, because the fuels have to travel through thousands of miles of pipelines, and they have to travel on our highways, they have to travel on our railroads. So if people are determined to stop them from doing that, and are willing to take the legal and physical risk to put themselves on the line and in the way, we can make sure that we stop “business as usual.”

Kathleen: One of your support people said, “I used to think of these companies as so powerful, inevitable, invincible. What tickles me is how fragile and vulnerable and frail they are. These pipelines are thin, twenty-eight inches. Two and a half million miles of them. Tens of millions of people who care about clean water and a future for their kids. Do the math.”

That kind of talk shakes me—this notion that we could stop the oil companies from doing so much damage to the future if we would only try—because it brings up the problem of complicity. If I see a harm, and I can prevent it, and I don’t stop it, then I am complicit in that harm. Think of the moral obligation to save a drowning child or stop a rape. Or to make it impossible for the fossil fuel companies to wreck the world.

Emily: If we make it impossible for them to go about business as usual, we remove the implicit permission that we have given. This seems to me to be a moral obligation.

Courage

Kathleen: But how much can a person ask of herself and, by extension, of her family—is going to jail for decades too much to ask? Your action might be a beautiful, symbolic thing, but not if it destroys you or silences your voice. Let’s talk about fear and the calculation of consequences. Were you afraid out there on the prairie? Are you afraid now?

Emily: People keep saying that we’re brave, we’re heroes, but I don’t feel brave at all. I dread the thought of going to prison. But I took part in the action in full awareness of these risks because of the risk that Enbridge and other tar-sands companies are taking. If the world’s scientists are correct, what really flows through those pipelines is the end of human history. I’m much more frightened of climate change than I am afraid of jail.

Annette: I had made my decision in advance, so I can’t say I was feeling any fear in the moment. The hope of giving my children a future outweighed the fear that I would spend a year or two in jail. But I’ll tell you when I was afraid: the first time I took this sort of action, a couple of years ago when I chained myself on the railroad tracks to protest the oil trains—just sitting there chained to a barrel, with an oil train waiting to come through.

Ken: I was feeling full of fear, but then I decided that the best way to deal with fear is to practice doing what you’re afraid of. So I stood in front of a gas pump, like Bill McKibben, until I got arrested and went through the whole process. I think anybody who wants to learn how to go to jail for what they believe in, they can just go practice.

Kathleen: Interesting that Aristotle says that too—that if you want to acquire virtuous character traits, the only way is to go out and act virtuously. You practice and after a while you become a virtuous person.

Michael: I was terrified that the law would be waiting for us when we showed up. But then I visualized myself stopping the car, getting the bolt cutters out, walking up to the sheriff, and saying, “Look, I’ve come a long way to do this.” But there was no sheriff, and it became clear that I was at the right place at the right moment in history. Look at these hands! These hands! They cut off the Keystone pipeline!

Good Faith

Kathleen: What does it feel like, after all that fear and preparation, to break into the chain-link enclosure, walk past the no-trespassing sign with bolt cutters in your hand, cut the chain, and start turning that big wheel? One of your videographers said that it was “shockingly easy.”

Annette: It felt joyful. Alice Walker says that resistance is the secret of joy, and I have found that to be so true.

Leonard: I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to get the valve closed before sheriff deputies arrived. I really didn’t get in touch with the joy until I was actually able to get the valve closed. I felt a deep sense of peace while I waited for law enforcement to show up.

Michael: I remember just feeling amazed that I was seeing a sign that said KEYSTONE PIPELINE, and that I was going to turn it off. I’ll never forget how long it took to turn that giant wheel, and I wished I’d been doing some upper-body training. But we turned it off. You know, that was 590,000 barrels per day, going under my feet. Then none at all.

Ken: I remember thinking, “We are alive! There is no part of us that has to shut down. We are psychically free!” It was a wonderful sense of freedom. I had been working for forty-odd years on climate change, all the time pretending that the work was making a difference. When I shut the valve, I felt a significant change. Nothing I had done on climate change up until that time was as much fun as turning this one damn knob.

Kathleen: I think that you are talking about what the French existentialist philosophers called “bad faith”—lying to ourselves, pretending that we are good people while we are doing so much harm and letting so much harm happen around us. There’s a terrible imprisonment in hypocrisy. The joy of true freedom comes when we face the truth squarely and take ownership of our responsibilities. You have felt that joy, Ken, as the rest of us perhaps have not.

Ken: Maybe so. My hero Václav Havel said something about “living in truth.” You remain engaged with the reality of what is happening, you don’t hide yourself from the suffering of it, and you do the best you can to address it. So as painful as it is, I prefer to stay tightly connected to reality, and then act appropriately.

Truth

Kathleen: The Beautiful Trouble website says that direct action can have many goals: “To shut things down; to open things up; to pressure a target; to re-imagine what’s possible; to intervene in a system; to empower people; to defend something good; to shine a spotlight on something bad.” What were your goals?

Michael: To stop the river of poison for once, and get caught. To be arrested. To go to trial and prove that defending life as we know it is no longer a crime. It is a necessity.

Kathleen: You were willing to go to jail in order to have a chance to make a necessity defense?

Leonard: Right. It wasn’t just shutting down the pipelines that we hoped to accomplish. We planned from the outset to go forward with jury trials. That would give us something like a year to communicate the emergency, using the action and courtrooms as a platform for getting the message out.

Annette: We all plan to use the necessity defense, which is a long shot. It’s saying that we had no alternative but to do this, that it was an emergency. Yes, we committed a crime, but it was a lesser crime than what is being committed against the planet.

Michael: If you are walking down the street and you see a house that is on fire and you hear a baby inside, what do you do? You don’t say, oh dear, it’s against the law for me to break into the house. You “bust out the windows and jimmy the door,” as Emily says in one of her poems, and you get the baby out. If you are arrested for breaking and entering, the necessity defense is that the harm you did was necessary to prevent a greater harm.

Emily: To make a necessity defense, you have to show, first, that you have exhausted all other options; second, that the harm was not one that you created yourself; third, that the harm was imminent; and four, that you had a reasonable belief that what you were doing would stop the harm.

Kathleen: So let’s take these one by one. Have you exhausted all the other options?

Annette: I am sixty-four years old. I have signed petitions, I have testified at hearings. I have personally met with politicians at all levels. I have marched in the streets—in short, I have used every legal means available to me. But what I have learned is that our political system is utterly unresponsive to the grave threat to our existence that climate change represents, so it is up to us to stop the fossil fuel industry from continuing to conduct business as usual.

When I look my grandchildren in the face, I want to be able to say that I did everything in my power to make sure they have a future. It won’t do to say, “I ineffectually petitioned my political leadership.”

Emily: There has never been a movement for social change that succeeded by people simply being good people and attending to their daily lives. To the degree that we are able, we all have to take risks.

Kathleen: But what about working with the mainstream environmental organizations?

Ken: I was a professional staff person for Greenpeace and the State Public Interest Research Groups for twenty years, and I was cofounder and president of the National Environmental Law Center. I believe that a great deal of the fault for where we are is because those of us who had a professional responsibility to create the fight early on avoided an immense challenge.

We held a series of polls in the late ’90s. Twelve or so environmental organizations paid for this. The pollsters said that people don’t really want to think about climate change and when you talk about it, they get depressed. So we followed a strategy for twenty years that involved lying to the public, not talking about climate change, not telling people what the problem is.

We—US environmentalism—made a decision not to put out the truth and also not to contest for the hearts and minds of people on this matter, especially in the center of the country. Even though deniers were going out with horrendous stories, we did not go out and try to fight that. We thought we could lie about the problem, negotiate with the fossil fuel companies, and come up with a technocratic policy solution around the margins. It was a complete fantasy.

Kathleen: Has the recent election changed this?

Ken: From the climate perspective, there may be a sort of silver lining in the election, in that it clarifies a lot of things—including the fact that the fossil fuel industry effectively runs US energy policy. Now we’ve got Rex Tillerson as secretary of state, but ExxonMobil has effectively been in charge for decades.

Kathleen: The second condition for the necessity defense is a tough one. Can any of us honestly say that we have not created global warming ourselves, by our choices as consumers?

I personally think this charge is completely bogus—if I can insert myself here. I think it may be one of the biggest triumphs of Big Oil, to make consumers blame themselves for climate change because we are the ones who are burning the fossil fuels—even while the corporations are spending billions to make sure that we have no alternatives.

They build and maintain infrastructures that force consumers to use fossil fuels. They convince politicians to kill or lethally underfund alternative energy or transportation initiatives. They increase demand for energy-intensive products through advertising. They create confusion about the harmful effects of burning fossil fuels. They influence elections to defang regulatory agencies that would limit Big Oil’s power to impose risks and costs on others. They do everything they can to be sure that people have no choice but to participate in the oil economy. And then they blame people for burning the fuels.

Michael: That said, we still have to take some bold and courageous actions to reduce our emissions. Our kids will not survive our hypocrisy.

Annette: But even if all of us who were involved in this fight foreswore fossil fuels and went to live in a cave, it would not change the system and the planet would fry anyway. So I find the argument to be very much a red herring, a false sort of argument.

Kathleen: Let’s look at the third condition for a necessity defense. Can you say that the harm is imminent, that is, about to happen?

One of the members of your support team said that “it’s important for people to know that climate change is with us now, and here is what it looks like. Because people will run out of water, climate change looks like the Flint water crisis. Because climate change will cause a massive displacement of people, it looks like the Syrian refugee crisis. Climate change will create a kind of xenophobic politics that feeds off the baseless fears of people who don’t understand what is happening, or do understand but don’t understand how they can take agency in it. That’s all with us right now.” What do you think?

Leonard: We’re out of time and we can see that there is no hope that our leaders have the resolve and ability to immediately and dramatically reduce carbon emissions. If I do nothing, if all the millions of other American citizens do nothing, our reductions in carbon emissions, if they ever come, will be too little, too late.

Kathleen: Well then, number four in the necessity defense—do you have reason to think that your actions might affect the trajectory of climate change?

Emily: I believe we’re coming to a moment when years of effort suddenly cohere and people pour into the streets. Then you, I, and our friends can bring down Exxon and spill its pockets to the people who are trying to rebuild the world. What will it look like, how quickly will things change, when people understand that we have this power?

If I do nothing but organize, vote, write, speak, I will see hideous things before I die, things that have already begun: countries imploding, hundreds of millions starving and displaced, entire ecosystems collapsing. We all will. When we are old, what will we wish we had done?

To be honest, I’d love to be able to lead a quiet life right now. E. B. White has a great quote about having to choose, every day, between saving the world and savoring it. But not to work on the saving at this moment in time would be to shrug off responsibility for the very world I was busy loving, at its greatest moment of crisis.

Compassion

Kathleen: So we come to love. You have said that your team approached this action with a spirit of love and grief. What does love have to do with this? Or grief? Or are they the same thing?

Leonard: I have grandchildren. I feel the threat of climate change viscerally. It’s as though someone is coming in to our house and threatening our children, our loved ones, our community. I can’t do nothing. In fact, that’s the most excruciating thing, to feel helpless. So finding what we can do is the only choice we have.

If we don’t take action, everything we love is completely threatened and ultimately will be destroyed by this system we have, the system that values profits over everything.

I have come to believe that our current economic and political system is a death sentence to life on Earth. Direct action is my act of love.

Emily: The French existentialist Albert Camus wrote, “I understand here what is called glory: the right to love without measure.” Maybe this is what I am looking for. I deeply love this world as it exists right now. I feel personally responsible that other people are suffering and that other species are suffering. And I don’t feel that inaction, looking away, is moral.

Kathleen: I suppose that grief is a measure of that love, isn’t it? That the more we love the little children of all species, the spawning salmon, the light through aspen leaves—you can name whatever you want—the more grief we feel when we witness their suffering.

Ken: I think it’s important that our approach to empathic action carries love for the people who are on the other side of it too and distinguishes the people from the structures they work in. This doesn’t mean there aren’t evil people who are doing evil things. But as best we can, we need to carry this forward with an appreciation of people, with as much love as we can find, for the people who are opposing us.

Leonard: Yes, it’s really important that we not only be nonviolent in a physical sense, but we also must be nonviolent in terms of our attitude and our verbal interactions. Respect and dignity are part of human rights. So when I’m taking direct action, it’s with respect for those people who are doing the harm that I’m putting myself in the way of. Compassion is the most powerful part of this kind of nonviolent direct action. That’s how we can triumph over corporate greed and remove the fossil fuel industry’s social license to profit at the expense of life.

Hope

Kathleen: There are so many different stories we can tell about Earth’s emergencies. There are economic and moral narratives, narratives of hope and despair, life and death. What sort of framing is most likely to move people to action?

I know that the appeal to fear is a very strong one, and we have certainly seen it have a strong effect in the last election. But the appeal to hope is a strong one too, the faith that we can do this, we can make this turn. In fact, one of your support people said, “When I started seeing people organizing to stop particular projects, what I saw was an opening of an imaginative space in our politics and a way of making the argument that we, as people, can stop and must stop the fossil fuel infrastructure. So for me, that’s part of the hope—the possibility of concrete actions.”

Ken: Hope is important, hope is vital, but also I think sometimes the dialogue of hope can lead to greater complacency rather than action. If you’re going to hope for a future, then damn well fight for it. The time for hoping someone else is going to save the world for us is quite long past.

Leonard: The truth is that there are more jobs per dollar for investments in alternative energy than fossil fuels. If we could just remove the obstacles and let people go and do the work to make this shift, we’d be on our way.

Michael: Most of the people that I’ve met who are taking a consistent courageous part in the movement can talk to you about the moment when they lost hope, when they reached despair, and then they woke up the next day and said, “Okay, now what?” I think that despair is a critical ingredient for facing the existential emergency we inhabit. This tragedy overwhelms the mind’s capacity to comprehend. Taking action is the only antidote, the only reason to hope.

Kathleen: So doing something tangible helps people hold an outcome in their minds and feeds their imaginations. That might be what Joanna Macy means by “active hope.” But hope is hard to hold onto, because it depends on a vision of outcomes—you hope to change the world, which is something over which you have very little control.

Ken: What we did was direct action, not a protest. We actually shut down a piece of the American petrochemical structure. But there’s no real way to know what the outcomes are, because this will propagate in a variety of ways, spiritual as well as political.

Emily: To be honest, I’m not sure what I hope for, except that humans can be as loving and sane and brave as possible in the coming decades—to each other, to the world. And I look a few thousand years into the future, sometimes, to think about how life, with or without us, might start to reestablish something like the abundance and magic that’s here now. Some of Earth’s creatures will have another chance; we’ll be among them only if we act with a really fierce resolve right now.

Integrity

Kathleen: Afrin Sopariwala, a member of Climate Direct Action, said in a Democracy Now interview that “people have taken this risk—and these are ordinary people. These are parents and grandmothers, concerned citizens, who, after years and years of all kinds of different legal actions . . . came to a point where they felt morally compelled to [act].” In what ways was your decision to act a moral decision, as opposed to a merely pragmatic one?

Ken: We are methodically, with full awareness and in the presence of acceptable alternatives, destroying the conditions that allow the wild riot of diverse life on this planet and that have made civilization possible, for reasons of greed, fear, and lassitude. Our only hope is to step outside polite conversation and put our bodies and ourselves in the way.

Annette: Even if you are not in a position to risk arrest, there is a role for everybody in this kind of direct, dramatic action. Everybody has something to contribute: food, travel support, organizing tours, public outreach, coordinating with churches, organizing, nurturing and healing, networking. We could not have done what we did without a lot of support behind the scenes.

Kathleen: I think that’s an important point. The consequences of a felony jail term are serious, as the history of direct action movements tells us. When I was teaching, I didn’t advise my students to take these risks. But I did tell them that there are many, many ways to be involved in direct action, and they are all important.

Annette: I would say, though, that if you are an older white person, this is your job. Those of us in privileged positions are not likely to be beaten or killed by the police, but young activists and people of color don’t have the safety that we have. We no longer have jobs to worry about. We no longer have children at home. If risks have to be taken, we have to take them.

Michael: I take to heart the words of Chief Arvol Looking Horse. “Did you think the Creator would create unnecessary people in a time of such terrible danger? Know that you yourself are essential to this world. Understand both the blessing and the burden of that. You yourself are desperately needed to save the soul of this world. Did you think you were put here for something less?”

Photographs by Steve Liptay and Jay O’Hara.

Comments

As a teacher, climate activist and writer, I believe this article exemplifies our responsibility to one another and creation. In every community, thoughtful, articulate elders such as these can be found, and I hope this article reaches many of them and inspires them to do likewise. They can’t put us all in jail…or if they do, at least we will have one another and our personal dignity intact. Thanks for writing this–

Planet Earths 1st Responders, Climate Collapse Crusaders, spreading common sense and compassion wherever they each roam. Quite frankly, if not obvious, super hero’s in a time of near utter and complete maddness then has consumed the minds and lives of the human race, that is led by its nose by shiney and new.

The planet needs more 1st Responders like these beautiful and caring Beings, human and Spiritual. There is a teaching in all of this, lots to be learned by example of these action steps and manuevers.

I applaud each who thought of this, those who participated and contributed to it blessing and healing act, beautiful acts of kindness, awareness, alertness, forgiveness, compassion, and empathy are heartfelt, and what is needed in this time of weather whiplash, climate collapse, and military escalation to justify the need and use of more fossil fuel.

My arms extended and hands held higher, out of respect, and regard that i have for 1st Responders of Planet Earth.

This globe, our star , this ship, we need and live on and call home, is on fire, and in dire need of 1st Responders to step up, stand up, and speak up for action and achievement of our goal, and that is to wake the family, wake the neighbors, call 911, grab a hose, grab a bucket, grab an pail, and help me put this Fire out, because it is the only house we have to live in!!

It is All about the water at this point in time,….each and every drop counts and matters…..each

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.