ON A SOGGY September afternoon in southeast British Columbia, Nancy Newhouse swung her truck through a bank of pearl-colored fog and bounced to a halt on the shoulder of Highway 3A. Newhouse, Tom Swann, and I emerged into the cold mist, stepping carefully around the puddled ruts carved in the pullout. A convoy of logging trucks, their beds heavy with timber, sprayed mud at our shins. Adjusting our raingear, we began trudging north along the highway; to our left, a screen of cedar, spruce, and Doug fir shielded the valley below. After a hundred yards, the curtain thinned, and Newhouse stopped.

“There it is,” she said, the hood of her Nature Conservancy of Canada raincoat pulled low over her eyes. She pointed through the trees, toward the floor of the Creston Valley. “There’s the corridor.” I followed her finger, baffled. Sorry, I wanted to ask, but where’s the corridor? I searched in vain for signage. A non- descript swath of grainfields glimmered through the shifting fog. The land lay flat, furrowed with oats. The brown arm of a dike, built to stave off the floodwaters of nearby Duck Lake, wormed across the property.

Though the land appeared mundane to my human eye—Yellowstone it wasn’t—from a grizzly bear’s standpoint you’d be hard-pressed to find a more important parcel in North America. This humble polygon of farmland, dubbed the Frog Bear Conservation Corridor, was a crucial piece in a two- thousand-mile puzzle, a bridge that would allow isolated clusters of Ursus arctos horribilis to mingle and mate. “This movement corridor is well known,” Swann, Newhouse’s colleague at Nature Conservancy of Canada, told me as raindrops pooled in his trim white beard. “The science is clear.” That science was why NCC had recently purchased and protected 679 acres of the Creston Valley. Though the land’s $2.5 million price tag was steep, Newhouse and Swann had help: over half the funds had come from the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, one of the world’s most ambitious wildlife groups.

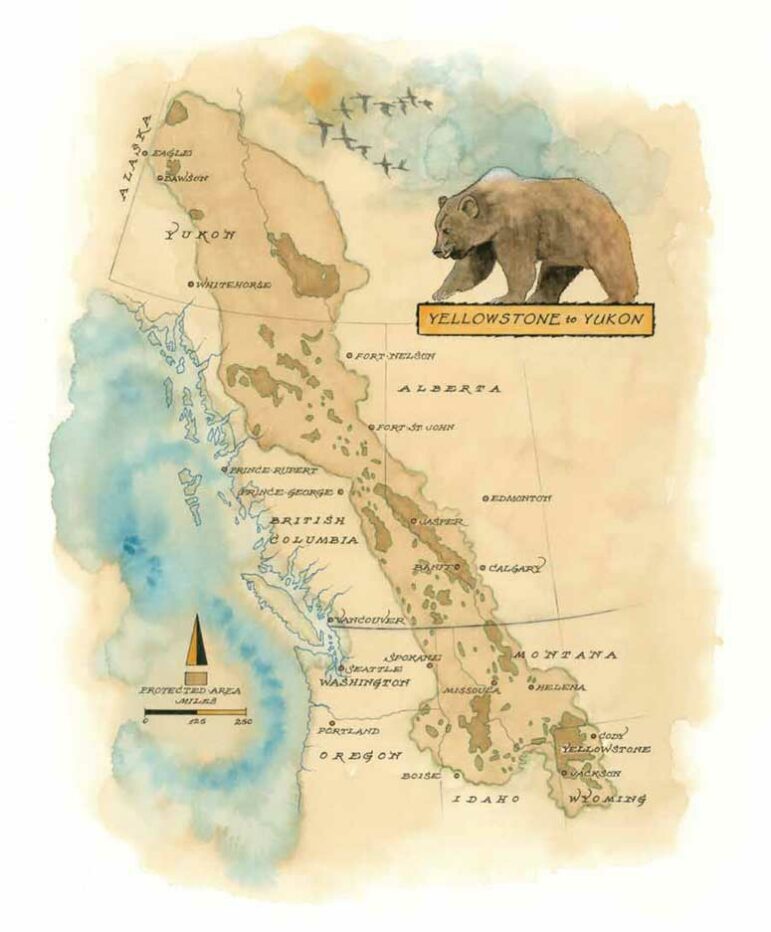

The vision of Yellowstone to Yukon, or Y2Y, is jaw-dropping: Its leaders espouse a continentwide network of protected areas and corridors that would allow animals to wander unhindered through a landscape the size of France, Spain, and the United Kingdom combined. The organization’s advocates dream that the effort will preserve migration routes for caribou and wolves, link pockets of far-ranging creatures like wolverines, and help animals of all sizes flee northward in the face of climate change. The group’s totem, however, is the grizzly, whose expansive habitat requirements make it a useful umbrella for protecting other species. If an ecosystem can support bears, it’s probably healthy enough for everything else.

The acquisition of those 679 acres represents the apotheosis of Y2Y’s approach to conservation, in which habitat connectivity reigns supreme. For a century, environmentalists focused on protecting scenic places—the peaks and ridges that define, say, Glacier National Park—at the expense of valley bottoms, the fertile areas we’ve commandeered for crops and towns. John Muir wouldn’t have been much impressed by the Creston Valley. “Why would you preserve flat grainfields when they’re not biologically rich at all?” Harvey Locke, Y2Y’s founder, asked me later. “Only if you understand that they’re absolutely essential to the functioning of the landscape.”

Just as Frog Bear isn’t classically beautiful, neither is it remote: the town of Creston lies just a few miles south. As it turns out, grizzlies and humans share similar taste in habitat. For wildlife, the valleys that we’ve colonized are natural travel corridors, each feeding into the next, sewing landscapes together. The frontlines in the battle to reconnect North America fall at these fragile margins, the delicate interfaces where wild ecosystems and human settlements collide. The key to conservation, as practiced by Y2Y, is to unplug the bottlenecks created by civilization. Thinking big is good, but thinking smart is better.

“Amazing, isn’t it,” said Swann, gazing out over the gray meadows. “You protect all that land, and it comes down to this.”

ON THE MORNING of June 6, 1998, a sandy-haired Canadian named Karsten Heuer heaved a backpack bulging with snowshoes, ice axes, and fuel canisters onto his shoulders. He wore blue cargo pants and brown boots crisp from their packaging. As the sun climbed the Montana sky, he stepped onto a trail near the northern border of Yellowstone National Park and began to walk.

Heuer, then twenty-nine, had spent the last few years in Banff National Park, working as a ranger and tracking wildlife. But he had grander dreams. In 1993, he’d attended a presentation by an environmental lawyer from Calgary named Harvey Locke. Locke, then thirty-four, had just returned from a horseback trip through the Canadian Rockies, where he’d seen caribou, moose, and a parade of grizzly tracks. The abundance of large mammals heartened Locke, who, like many environmentalists, was coming to realize that North America’s protected areas were too small and scattered to sustain wildlife. A bombshell 1987 study in Nature had revealed that parks were hemorrhaging fauna: lynx had vanished from Mount Rainier, otter from Crater Lake, red fox from Bryce Canyon. Wildlife needed more room to find food and breed than most parks afforded; the smaller the park, the fewer animals it could support, and the greater the risk of extinction—after all, five moose are more likely to disappear than five hundred. Too many populations were isolated from immigrants that could bolster their numbers, and animals that ventured beyond park boundaries too often fell victim to cars and guns. Conservation’s leading lights believed that conjoining the continent’s fragmented wildlands was the only way to stave off collapse.

One evening during his trip, Locke had been seized by the connectivity zeitgeist. He’d crouched by a campfire and, in the margins of a topo map, scribbled the first lines of an essay espousing a chain of wildlife corridors throughout the Northern Rockies, from the Arctic Circle to Wyoming. Locke retreated into his tent and wrote through the night; by the time he’d emerged, he’d scrawled the words “Yellowstone to Yukon” for the first time. The response was ecstatic. Since the discipline’s founding, conservation biologists had functioned as an army of Dutch boys, desperately attempting to plug biodiversity’s leaky dikes, losing as many species as they saved. But Y2Y was different: proactive, bold, an antidote to despondency.

When Heuer first heard Locke’s vision, though, he was skeptical. He brimmed with questions: Would locals support the scheme? Was there habitat left to connect? Finally, he proposed a 2,200-mile hike: part ground-truthing exercise, part publicity stunt. Y2Y had captured imaginations, but no one knew if it could work. Heuer aimed to find out.

Starting from that Yellowstone trailhead, Heuer and a rotating cast of companions hiked, skied, and canoed through three states, two provinces, and one territory over eighteen months. Along the way, he was caught in an avalanche, stood his ground against a charging black bear, and gained as much elevation as summiting Mount Everest twenty times. Once a week, he threw on an oxford shirt and ducked into trailside towns to give talks and interviews. Timber and mining companies planted a stream of negative press before him; the day he arrived in Prince George, British Columbia, the newspaper blared, “80,000 jobs to be lost due to Y2Y.” Coal company flacks heckled him at his lectures. His sister-cum-publicist received a death threat. When Y2Y wasn’t being assailed by industry, it was mocked by Aaron Sorkin. In 1999, the TV show The West Wing parodied Y2Y as the “Wolves Only Roadway,” the vanity project of humorless tree-huggers. After the greenies aver that the roadway would cost $900 million, they get laughed out of the White House.

IN SEPTEMBER 2013—fifteen years after the first footfall of Heuer’s hike, and twenty since Harvey Locke coined his phrase—a companion and I set out to see how Y2Y’s lofty vision was faring. Our trip was considerably less heroic than Heuer’s, as many of our predecessor’s experiences—dangling off an icy cornice, skis kicking wildly at thin air—were not ones we were eager to recreate. Instead of by hiking boots and snowshoes, we were transported by a 2002 Camry with a well-stickered bumper. The closest we came to peril were some perturbing check-engine lights.

In a way, though, our civilized mode of travel was fitting. To be sure, Y2Y’s anchors are still wildernesses like British Columbia’s Muskwa-Kechika, a remote biodiversity stronghold the size of Ireland. In 1993, just 12 percent of the acres within Y2Y’s borders were preserved; today, 21 percent are parks, and another 31 percent have other protections. That’s classic conservation: secure the wild stuff. During our 2013 tour, we’d see few of those places. Attempting to visit the Muskwa-Kechika by car would be like trying to survey the Mariana Trench from a kayak.

Increasingly, however, Y2Y’s battles are fought not in the backcountry, but in the boardroom. Locke’s preposterous idea now commands eleven full-time staffers, a $2.5 million operating budget, and over 200 partners—land trusts, activists, and scientists whose local activities are compatible with the larger vision of continentwide connectivity. Y2Y is effectively a relay race, in which each region is trying to hand off an intact landscape to the next: Yellowstone to the High Divide, the Waterton Front to the Canadian Rockies, Jasper to the Muskwa-Kechika. In 2013, Karsten Heuer became Y2Y’s president, the coach responsible for coordinating the race’s runners.

Heuer is a scruffily bearded man with a square, sturdy frame that looks well suited to a backpack. When I met him at Y2Y’s headquarters in Canmore, Alberta, he still seemed surprised he’d taken the job. He and his wife, the filmmaker Leanne Allison, had long maintained a half-feral lifestyle: They’d migrated alongside caribou above the Arctic Circle in 2003; in 2007, they rambled three thousand miles with their two-year-old son in homage to the writer Farley Mowat. But their peregrinations were now on hiatus, backburnered by fundraising and strategic planning from a second-story office above a bank and a Starbucks.

“I just got back from three days of meetings in East Glacier,” Heuer said as we sat down. He wore a rumpled plaid shirt; his voice was husky with a lingering cold. “One of the most spectacular landscapes in the world, amazing weather, and we were hunkered down in a basement with no windows. My every molecule was yearning to be outside.” Sometimes, when he travels for conferences, he brings a tent. As we talked, he sketched maps of watersheds on scrap paper, almost unconsciously, as though the Rockies had infiltrated the recesses of his brain.

Though Heuer was then only forty-two, he had applied for the job in deference to his own mortality: as he put it, “How was I going to make as much change as possible happen before I die?” To see why change was necessary, we needed simply to look out the window onto Canmore, a former mining community reborn as a tourism paradise. The town lies at the floor of the Bow Valley; beyond its borders loom the sharp peaks of Banff National Park. The layout fairly epitomizes traditional “rock and ice” conservation: abandon the steep slopes to wildlife, claim the hospitable flatlands for humans. For decades, any critter that ventured down from the mountains was greeted with a bullet.

As trigger-happy miners ceded to animal-loving outdoorsmen, though, wildlife began traversing the village again. Collateral damage ensued: cougars devoured pets; a child was nipped by a coyote; a grizzly killed a jogger. “We’ve encroached on an important corridor for feeding, breeding, and movement,” Kim Titchener, then-president of a local group called BearSafety, told me. “This place is a smorgasbord of crazy conflicts.”

To alleviate clashes, Canmore has designated several wildlife corridors—flat swaths of land, several hundred meters wide, that circumnavigate the town. Preventing those pathways from being clogged by condos and golf courses has required constant vigilance; just before I arrived in Canmore, a developer had temporarily scrapped plans for a new megaresort, in part due to Y2Y’s campaigning. Though years of surveying have demonstrated that wolves, bears, cougars, and elk indeed frequent the corridors, animals don’t always stick to precedent. “You’ll read in the literature that grizzlies need a half-kilometer of buffer, and then you’ll hear about one on somebody’s porch,” one ecologist told me with a rueful grin. Even the eminent biologist Bill Newmark, author of the 1987 Nature study that helped catalyze Yellowstone to Yukon, doubted that wildlife would comply with Y2Y’s best-laid plans. “It’s a corridor in people’s minds,” Newmark opined in 2009. “Whether or not animals really use it is another question.”

Who, I wondered, was asking the animals?

HARVEY LOCKE may be Y2Y’s human progenitor, but even more influential was a wolf named Pluie. In the early ’90s, Pluie wandered from Banff to Glacier to Idaho and back, an area ten times the size of Yellowstone National Park, her radio collar’s far-flung transmissions testifying to parks’ shortcomings. Pluie served as both mascot and guide, alerting scientists to important corridors and offering a flesh-and-blood illustration of connectivity’s importance.

Though no animal has achieved Pluie’s iconic status, Bob came close. Bob was a bear—“the healthiest, strongest motherfuckin’ specimen you’re ever gonna meet,” Michael Proctor recalled fondly as we walked the rocky lakeside beach near his home in Kaslo, British Columbia. “He made me feel like a marmot.” Proctor—a wiry biologist whose intense gaze suggests that he could hold his own in hand-to-claw combat with a grizzly—caught Bob in a foot snare in 2006 and fixed a radio collar around his giant neck. Then he waited to see what Bob would do.

Bob was a member of the Purcells-Selkirk grizzly population, six hundred bears that roam the mountains of southeastern B.C. near the U.S. border. The population’s boundaries are largely defined by Highway 3, to the south, and Highway 1, to the north. For bears, the human settlements that have sprung up along those thoroughfares represent an oft-fatal temptation. “Orchards, garbage, livestock, cat food—it doesn’t take much for a bear’s nose to draw ’em into trouble,” Proctor said.

The Purcells-Selkirk population is not only hemmed in by humanity, Proctor fears it will someday become internally divided, fatally fractured into a concatenation of micropopulations. A nearby cluster of bears, in the Selkirk Mountains, has as few as thirty grizzlies. It’s a textbook conservation problem: The region’s viable habitat risks deteriorating into an archipelago, surrounded by an ocean of civilization. Absent corridors, the smallest populations are in peril of washing away.

Re-enter Bob. In April 2007, he awoke from hibernation and rambled down the Purcell Mountains toward the Creston Valley, where new greenery was already springing up. There, he hid during the day and emerged at sundown to dine—in the same drab, inglorious fields that Nancy Newhouse and Tom Swann had showed me. Proctor was taken aback: the area’s blandest habitat was being patronized by its most virile resident. Even better, the Selkirks lay just a few miles west. If bears were foraging in the valley, they might also be using it to shuttle between the Selkirks and Purcells. At this innocuous spot, connectivity seemed possible.

Proctor set more traps in the valley and soon caught a female, dubbed Rebecca, who did Bob one better. Not only did Rebecca enter the Creston Valley, she crossed it, spending two weeks in the Purcells before returning to the Selkirks. Proctor relayed his findings to Swann and Newhouse, and, armed with that evidence, Nature Conservancy of Canada—with Y2Y’s financial assistance—eventually bought the land from Wynndel Box and Lumber, the sawmill that owned it. Under the deal’s terms, the Frog Bear Conservation Corridor would remain farmland, with the conditions that it couldn’t be subdivided or built upon.

Michael Combs, Wynndel’s CEO, was pleased with the agreement he’d struck. “How often do you have the opportunity to save a species, protect farming, and, obviously, get a return on the land?” he asked me. Plenty of corporations within the Northern Rockies evince Combs’s brand of compassion-tinged pragmatism. Fording Coal, whose flacks once protested Heuer’s talks, has ceded to Teck Resources, by one metric Canada’s most sustainable company; no matter how cynical you are about a coal company calling itself sustainable, conservationists agree Teck is far more pleasant than its predecessor. Tembec, among southeast B.C.’s dominant logging companies, has donated thousands of acres of easements to NCC. By any measure, the region is light-years removed from the distrustful 1990s, when the Union of British Columbia Municipalities passed a resolution condemning Yellowstone to Yukon.

Nonetheless, Tom Swann described NCC’s relationship with Yellowstone to Yukon as a “delicate dance.” After all, NCC prides itself on relationships with loggers, miners, and ranchers, and Y2Y’s name still isn’t golden everywhere. In southern Alberta, where grizzlies are trundling onto the prairies for the first time in a century, I met with ranchers who were modifying their operations to accommodate bears—installing grizzly-proof grain bins, better disposing of dead livestock, giving up raising sheep. Y2Y and others have nurtured those efforts, and one environment-minded rancher had recently held a seemingly productive meeting with conservationists. Bears were more numerous than people realized, the rancher told the greens, and emerging science corroborated his observations. The conservationists seemed to agree—but in subsequent quotes in the media, they continued using low-ball population estimates.

“They’re looking at the same stats as us, but they pick the numbers they want to use,” the disappointed rancher told me. “My opinion is that if they tell the whole story it won’t look as bad, and so they’re not bringing in as much money.”

Whether that’s fair or not, Y2Y’s greatest asset is indeed its narrative. The constant risk, however, is that the grand story becomes grandiose, consuming local efforts that, in many cases, predate Y2Y’s involvement. That’s why Michael Proctor keeps himself at arm’s length—not because he’s a glory hound, but because the perception that his research is driven by Y2Y’s agenda could alienate some collaborators. “Just make it clear in your article that I’m an independent biologist—I don’t work for them or anybody else,” he told me with a wry smile. “And if you mess that up, remember that I’m very good at setting leg snares.”

THREE WEEKS LATER on my Y2Y road trip, I found myself clinging to an upper limb of a gnarled apple tree, picking fruit for conservation. I was in a backyard in Missoula, Montana, three hundred miles south of Canmore as the golden eagle flies, on a house call with Monica Perez-Watkins, office manager at the Great Bear Foundation. Perez-Watkins was perched in the branch above me, poking at a stubborn apple with a telescoping pole. With a deft flick, she dislodged the red globe; it caromed earthward through the foliage and came to rest in the grass. We clambered down to gather the fallen fruit.

“This is the thirty-second site of the season,” said Perez-Watkins, a lanky woman in a black sweatshirt and enormous sunglasses, as we scooped apples into a paper bag. “And since there’s usually more than one tree per site, we’ve probably done”—she paused to perform some mental math—“almost one hundred trees.”

The link between collecting fruit and connecting habitat is not, upon first blush, obvious. On the north side of Missoula, where the Rattlesnake Wilderness sweeps down to meet suburban development, abundant apple trees often seduce black bears in fall, when the fruit ripens and the creatures are prowling for calories. To forestall conflicts between ursids and people, the Great Bear Foundation, one of Y2Y’s partners, operates a program called Bears and Apples, through which staff and volunteers pick bare the trees of willing landowners. (The apples go to cider presses, food banks, and homeless shelters.) Thanks partly to the foundation’s efforts, said cofounder Chuck Jonkel, the once-fraught relationship between humans and bears has, at least in the Rattlesnake, de-escalated into something resembling harmony. “It takes a long time to get people to not only live with bears, but to behave,” Jonkel told me. “It’s like driving a car for the first time—there are rules you have to learn.”

Imparting and enforcing those rules—pick your apples, lock your dumpsters, replace the wooden walls of your grain bin with aluminum—is not, perhaps, the sexiest part of connectivity. Yet if open garbage and untended chickens lure wildlife into the deadly embrace of civilization, conservation easements and wildlife crossings will be nothing but bridges to nowhere. Within the vast expanse of Yellowstone to Yukon, the apparently mundane field of attractant management has produced some of the most intriguing innovation. In Montana’s Blackfoot Valley, for instance, I inhaled the odor of rotting meat at an electric-fenced facility where ranchers were composting livestock carcasses within towering piles of wood chips. For years, dead cattle had simply been hauled off to ranch boneyards, where they inevitably drew grizzlies into trouble; in 2003, however, a collection of local ranchers called the Blackfoot Challenge began transforming the corpses into compost, which the state now uses in roadside revegetation projects. According to Seth Wilson, biologist at the Blackfoot Challenge, the arrangement has reduced grizzly conflicts by some 90 percent. “Getting dead carcasses off the landscape is low-hanging fruit for large carnivore conservation,” he said as I inspected a stray femur.

As Y2Y and its satellites have pioneered new approaches, they’ve become models for large-scale connectivity efforts on six continents. The European Green Belt, a network of habitat that was incidentally protected by the Cold War’s Iron Curtain, will someday run north to south through twenty-four countries, from the Barents Sea to the Aegean. “Peace parks”—border-spanning protected areas that allow wildlife to migrate unfettered by geopolitics—have sprung up in Africa. A proposed Atlantic Megalinkage would run from Florida to Quebec, joining ecosystems like Georgia’s coastal plains and Vermont’s Green Mountains.

Some connections, inevitably, have collapsed: Paseo Pantera, an epic corridor planned for Central America’s Atlantic Coast, stumbled under the weight of its own bureaucracy. But more have flourished. There are vegetation connectivity projects in Australia; corridors between savannah and wetlands in Brazil; highway crossings in China, Mongolia, and Turkey. “I can say the name Y2Y just about anywhere on Earth, and people know what it means,” Harvey Locke told me. “Our idea isn’t the template that everyone else obeys, but it’s certainly the archetype.”

IN LATE OCTOBER, our trip ended where Heuer’s once began: Yellowstone National Park, where the buffalo roam and the SUVs idle to take their picture. At the entrance lingered pronghorn and elk, as comfortable around humans as household pets. The next morning, I glanced out the window of our cabin to see a burly gray wolf staring back. The wolf crouched like any domestic canid and dropped a ribbon of scat before vanishing into the timber.

No grizzlies, though. It made for an anticlimax: We’d spent two months obsessing about the ursine ghost in Y2Y’s machine, examining the electric fences and conservation easements that had been completed in their honor, like offerings left for a deity. Yet the closest we’d come to laying eyes on one was a tuft of coarse chocolate hair, snagged by a coil of barbed wire in northern Idaho.

We drove southeast from Grand Teton on the last day of October, the sun a red ball on the horizon. Cruising down the eastern slope of the continental divide, we rounded a curve to find a pickup parked in a pullout, the driver craggy beneath his cowboy hat. He lifted a finger from the wheel and nodded toward the embankment across the road. My companion slammed the brakes.

Atop the roadbank, where dirt hit timberline, lumbered a female grizzly, enormous muzzle swinging beneath the hump of her shoulders, haunches rippling under silver fur. Two German Shepherd–sized cubs trailed behind, snouts to the ground. A radio collar encircled the mother’s tree trunk of a neck. We snapped pictures and pondered our good fortune: there might have been, at that moment, a few grizzlies farther south in North America, but not many.

Back home, I called Dan Bjornlie, carnivore biologist with Wyoming Game and Fish; perhaps he knew the bear’s fate. I gave him the details and heard him typing, searching his database. “That might have been Bear 718,” he said at last. “She’d been hanging out around the pass.”

Though 718 hadn’t roamed much, other bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are on the move. The population has grown over the decades, from fewer than 150 to around 700, and as their numbers have increased, Yellowstone’s core has proved too small. They’ve pushed down the Wind Rivers toward Pinedale, down the Wyoming Range south of Jackson, east onto the plains past Cody. Four years in a row, Game and Fish has confirmed sightings in South Pass—closer to Utah than to Montana. To Bjornlie’s surprise, the bears are surviving their forays. “The rate of mortality hasn’t increased as fast as distribution,” he told me.

Yellowstone to Yukon certainly doesn’t deserve direct credit for Wyoming’s wandering grizzlies. Still, the needle has moved; whether Y2Y pushed it is, in a sense, beside the point. Two decades ago, any animal that strayed beyond park boundaries was liable to catch a bullet or get pancaked by a car. While those dangers linger, we’re better at coexisting with wildlife than at any time since wagons first rolled West. Even hidebound bodies like Alberta’s provincial government and the U.S. Forest Service are including corridors and connectivity in plans and rules. “If you try to connect all the dots, it’s sometimes hard to see the exact path,” Heuer told me in Canmore. “Did Y2Y have a part to play in those decisions? Absolutely. What specific part, and to what extent? I could never tell you.”

In the winter of 2015, Heuer bowed out from his own part in Y2Y. Though he cherished the mission as much as ever, being confined to a desk gnawed at him. He felt anxious; he stopped sleeping. Finally he quit, desperate to reacquaint himself with the lands and animals he’d tasked himself with saving. These days he’s leading the reintroduction of bison to Banff National Park, though he remains connected to Y2Y as an adviser and volunteer. “People see careers as linear things, but some explorers have to go up into the box canyon,” Heuer told me when last we spoke. He sounded liberated.

The patience to explore box canyons is a luxury that conservation doesn’t always have. The threats are perpetual and protean: there’s the fracking boom in British Columbia; the industrialization of Canada’s parks; the mining plan approved for the Yukon. Maintaining connectivity requires constant pressure. Sometimes, though, we can only set the stage upon which nature will perform. Grizzlies once ranged far beyond Y2Y’s borders—into Utah, Colorado, New Mexico. We’ll know Yellowstone to Yukon is working when it begins to feel small.

Comments

Fantastic read. Really. Nicely woven. Visual. Delectable vocabulary. A good yarn and a good perspective, on Y2Y.

Well written article Ben. As a resident of the Creston Valley I think you have placed the issues in focus. I will share this with many of my friends. It is hard to put your fingers on the Y2Y visision and it’s sucesses until the evidence is pointed out, thanks.

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.